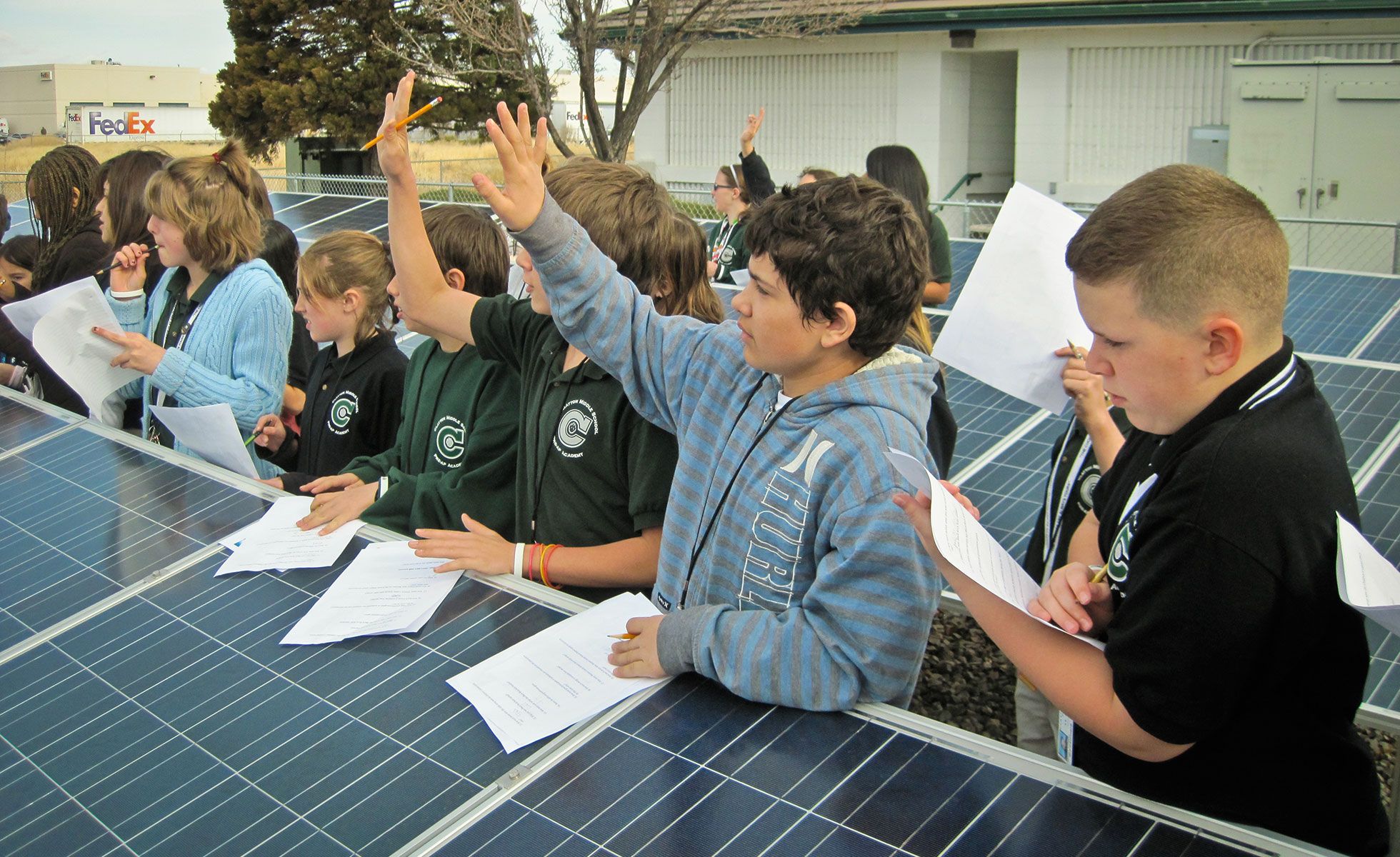

Middle school students visit a solar array. (Photo: BlackRockSolar via Flickr)

In spring 2014, the Toronto District School Board — Canada’s largest — embarked on a program of putting photovoltaic panels on more than 300 of its school buildings. When complete, it will create enough power to meet the annual needs of about 4,250 homes. But Richard Christie, senior manager of the board’s sustainability office, says the program generates far more than electricity.

The Solar Schools Project had its genesis in a pilot, launched in 2010, for which small (one- to 46-kilowatt) solar arrays were placed on 12 schools. Income produced through sales of this power helped establish the board’s Environmental Legacy Fund, which gives teachers $400 toward the cost of a $650 course in ecological education. “These courses will have a big impact on the [school] system,” Christie explains. “Ten years from now we’ll see a lot more principals who have environmental education as a priority because they took these courses when they were teachers.”

After the success of its pilot, the school board wanted to scale up. It created a partnership with renewables developer School Top Solar Limited, which commissioned assessments of the sunlight potential and structural integrity of hundreds of school roofs and assisted the board in submitting feed-in tariff applications to the Ontario Power Authority. In the end, the partnership was awarded FIT contracts to put solar panels on 311 buildings. But there was a catch: To accommodate the panels, many of the schools needed new or upgraded roofing.

Under the partnership, School Top agreed to repair or wholly replace the roofs — some of which were badly degraded — and install and maintain the solar arrays. In return, the board granted the solar developer a licence to use the space and receive the FIT contract revenue. The project’s scale is staggering: some 400,000 square metres of roofing will be replaced or fixed.

The solar roofs help kids overcome despair. Kids see that, with their help, we can change the world for the better.

Richard Christie

Also exciting is the fact the new roofs will come with insulation. (Prior to the project’s commencement, most Toronto public school roofs lacked this.) So the environmental advantages are multiple. “When looking at the solar roof program, people tend to focus on the benefits of solar electricity generation, and of course that’s there,” Christie says. “But perhaps an even bigger environmental benefit is the GHG reduction associated with reduced use of natural gas due to roof insulation.” The project is inspiring, even exhilarating, because it combines two key climate solutions: emissions-free power production and conservation of heating fuel. It brings us closer to attaining a central ecological objective: the creation of net-zero-carbon buildings.

Solar Schools has an educational component. “In Grade 6 science, kids learn about electricity,” Christie explains. “In 2011, the board created a new resource guide on electricity which talks a lot about solar. As schools get panels, kids’ interest in solar rises.” To further boost their engagement in the project, the board is setting up an online dashboard so students can see how much power their array creates and how much energy their building consumes.

The project’s greatest virtue may be its contribution to what I would call climate optimism. It reminds students that not all news is gloomy. Hopeful possibilities exist, and indeed some are taking root in their own school. “[The] solar roofs help kids overcome despair,” Christie says. “Kids see that, with their help, we can change the world for the better. This foundational experience is key.”