Severn Cullis-Suzuki, photo taken in 1989 in the Brazilian Amazon. (Photo: Cullis-Suzuki Family)

Ahead of the COP30 climate summit in Belém, Brazil, the David Suzuki Foundation spoke with Severn Cullis-Suzuki about her iconic 1992 speech in Rio de Janeiro, her family’s connection to the Kayapo people and her hope for today’s youth and COP30 delegates. The following has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

It’s been 33 years since you “silenced the world for six minutes” at the 1992 Earth Summit. If you could tell yourself, that little girl on the stage, what the world is like now, the challenges we’re still facing with climate and nature, what would you say to her?

I guess what I would tell that little girl is that things are going to get worse before they get better. The infrastructure has been put in place to really support extreme capitalism. The architecture of an economy and governance structure that will precipitate a lot of loss of nature and people. But one thing to really hold on to is that people — the majority of us — do believe in sustainability. They do believe in the importance of peace. I actually believe those things are universal. But our frameworks of capitalism are powerful. It’s going to get worse before it gets better.

Back in 1992, there wasn’t really such a thing as “viral videos,” not like there is today. But I suppose yours did go viral in a pre-internet sense. If you could cast your mind back to that time, when you were only 12 years old, what was the aftermath of that speech like for you?

After Rio, someone at the UN sent me a copy of the plenary speech. We got VHS copies of the clip made. We sent copies of these all around the world because people were sending us letters (not emails, letters!), requesting a copy of the interview of this speech they’d heard about. Over the years these turned into DVDs; we’d ask people to send a donation to cover the costs. Because this was all just before the internet. When the internet finally came out, people started uploading the video online. It kind of went viral, in pre-viral, pre-internet times; it’s fascinating.

Every few years there’s a spike of views, and it goes viral again. I think it was last year that one of the Kardashians posted a clip of it! With the rise of youth activism and the prevalence of youth voices in the media and social media, it’s also interesting to see that interplay with the Rio speech and what youth are doing. Youth have always been activists. Youth have always been on the front lines. Front lines fighting for their people, fighting, speaking truth to power. That is one of the most powerful roles of youth.

Youth have always been activists. Youth have always been on the front lines. Front lines fighting for their people, fighting, speaking truth to power.

Your dad, David Suzuki, said that it wasn’t until after the speech that he could finally soak in the magnitude of it all. I know it was so long ago, but if you could take us back to how you were feeling when you stepped on that stage. You don’t appear nervous at all. You were determined and, at times, angry. How did you feel when you were giving your speech?

The speech at Rio was the result of a year of work, of organizing, raising money and of so many people supporting me and my friends to get down to Rio. After two weeks of working at the summit, my friends and I were so practised at giving our message that I knew exactly why I was there. By the end of the conference, when I was given the chance to speak at a plenary session, I was very clear on my message. Yes, I was angry; I was very upset and because of this, I was able to really connect with the pure reason we were there: to represent the young generations and the future generations who had no vote at those meetings, who were not being represented politically, because even then the capitalist interests were so clear.

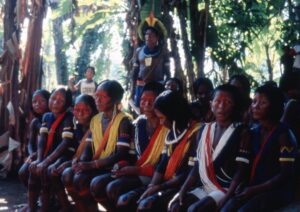

Severn Cullis-Suzuki visits the Kayapo people of Brazil, 1989. (Photo: Cullis-Suzuki Family)

Circling back to Brazil, as your speech in 1992 was in Rio, and COP this year will be in Belém in Brazil. Why does Brazil hold such a special place in your heart? What are your family’s ties to the Kayapo people of Brazil?

My family got involved because of my dad’s television series, The Nature of Things, where he made several films about the burning of the Amazon rainforest. He connected deeply with a Kayapo leader called Paiakan, and our families developed a very strong relationship. When he received death threats for his activism, he brought his family to Canada and lived with us in Vancouver for six weeks. When they invited us down to the Amazon to their village, we were honoured to be able to take them up on it the following year. It was absolutely formative to me, going into the Amazon, experiencing life without our money economy. I was about nine at the time.

But when we left, I witnessed the burning of the Amazon from the plane, and I realized the Kayapo people were in the centre of this. When I came back to Canada, I knew I had to do something. That’s when I started the Eco Club with my friends, which eventually, years later, went to the Earth Summit in Rio — again in Brazil.

But Brazil not only is important in my own story; it holds a great importance in the world’s ecosystem. We all grew up hearing about the Amazon Rainforest being lungs of planet Earth — we have this amazing source of oxygen for our planet, and it’s a massive, climate-stabilizing carbon sink. This year’s COP in Brazil is significant — not only being held in the Amazon, but at a time when the rainforest is going from being a net carbon sink and drawing carbon out of the atmosphere to now being a net emitter and not being able to absorb our pollution any longer. We have crossed a threshold and if we’re not talking about that in Belém this year, we are missing the point.

My hope is that in Brazil, in the country of “the lungs of the planet,” there will be an acknowledgment that these thresholds are being crossed.

Witnessing the burning of the Amazon from a tiny plane in 1989 (Photo: Cullis-Suzuki Family)

What is your message for the delegates at this year’s COP30? And what’s your message for the civil society and Indigenous people attending?

My hope is that in Brazil, in the country of “the lungs of the planet,” there will be an acknowledgment that these thresholds are being crossed. I hope that those gathered ask why something’s drastically wrong with how we’re addressing these problems. Last year we surpassed 1.5 degrees of warming on average of the planet. We promised as an international community at COP 21 in Paris 2015 not to let that happen! We celebrated that as an incredible achievement.

What does it mean that we make these promises that mean absolutely nothing? The United Nations and international law, these institutions are so clearly under threat. And our problems with the global environment is another part of this crisis of human governance. That’s what I want people to talk about at COP30. Because what we’re doing is simply not working. It doesn’t make sense for us to just keep going to COPs, keep attending these conferences, keep doing the same thing, keep negotiating and keep getting exhausted, if it’s not working.

For the civil society and Indigenous people, one of the things that would be very appropriate would be to hold grieving ceremonies, to have some kind of acknowledgement of the losses that we are witnessing and feeling. Once we’ve had a little bit of space to grieve, then I think we can start to build the new strategy that is going to help us in this new era find ways to survive because that’s what we’re in. A new climate chaos era is upon us. We need to prepare, we need to be ready and we also need to know what the new path forward is.

Severn Cullis-Suzuki receives traditional face painting from the Kayapo people of Brazil. (Photo: Cullis-Suzuki Family)

What’s your message to young people today. How can they find that galvanizing spirit that you experienced in Brazil and what are some suggestions for them to set the groundswell for this movement?

Young people today have every reason to feel angry, every reason to feel upset. With the amount of violence and loss that young people are seeing through the internet, as well as the pressures from the climate crises that we are all becoming connected to, it’s really important to find people and places where you can share that and process the loss. It’s coming for everyone; here in Canada, we are starting to see climate refugees in our own communities through wildfires. We really need to build up our support systems to help keep ourselves, our communities and our spirits strong.

We need to ensure that we are well, in a time when so many things seem dark. We can also find and connect with the communities of resistance in mutual aid, decolonized practice and solidarity movements that are all over the globe.

For instance, I’m so inspired by the Haida Nation, who this year got full recognition of title not only by the B.C. government, not only by the federal government, but by the Canadian courts. Title of Haida Gwaii belongs to Haida people, as it has been for over 13,000 years. Now, after a 100-year struggle, it’s recognized as such by the Canadian government. They are taking stewardship of their land back, with a philosophy that is different to the mainstream.

There are many examples of Indigenous Peoples reclaiming their power and stewardship of land that has been disrespected by today’s capitalist paradigm, and groups of humans actively working on alternative ways of being. I want young people to know that though today seems like this globalized, capitalist economy is the only economy, it is not the way it always has been. And still, in many places around the earth, in the pockets of resistance, economies look very different: gift economies, trade economies, socialist economies.

Don’t let anyone tell you that this is the only way it’s ever been, the only way it ever can be, because it’s so obvious that the current system isn’t working, and luckily the diversity of human species and cultures shows us that there’s so many different ways of living. So, find those people, find those ideas, start practising them, and you’ll find an incredible community of inspiration, as I have.

Don’t let anyone tell you that this is the only way it’s ever been, the only way it ever can be, because it’s so obvious that the current system isn’t working, and luckily the diversity of human species and cultures shows us that there’s so many different ways of living.