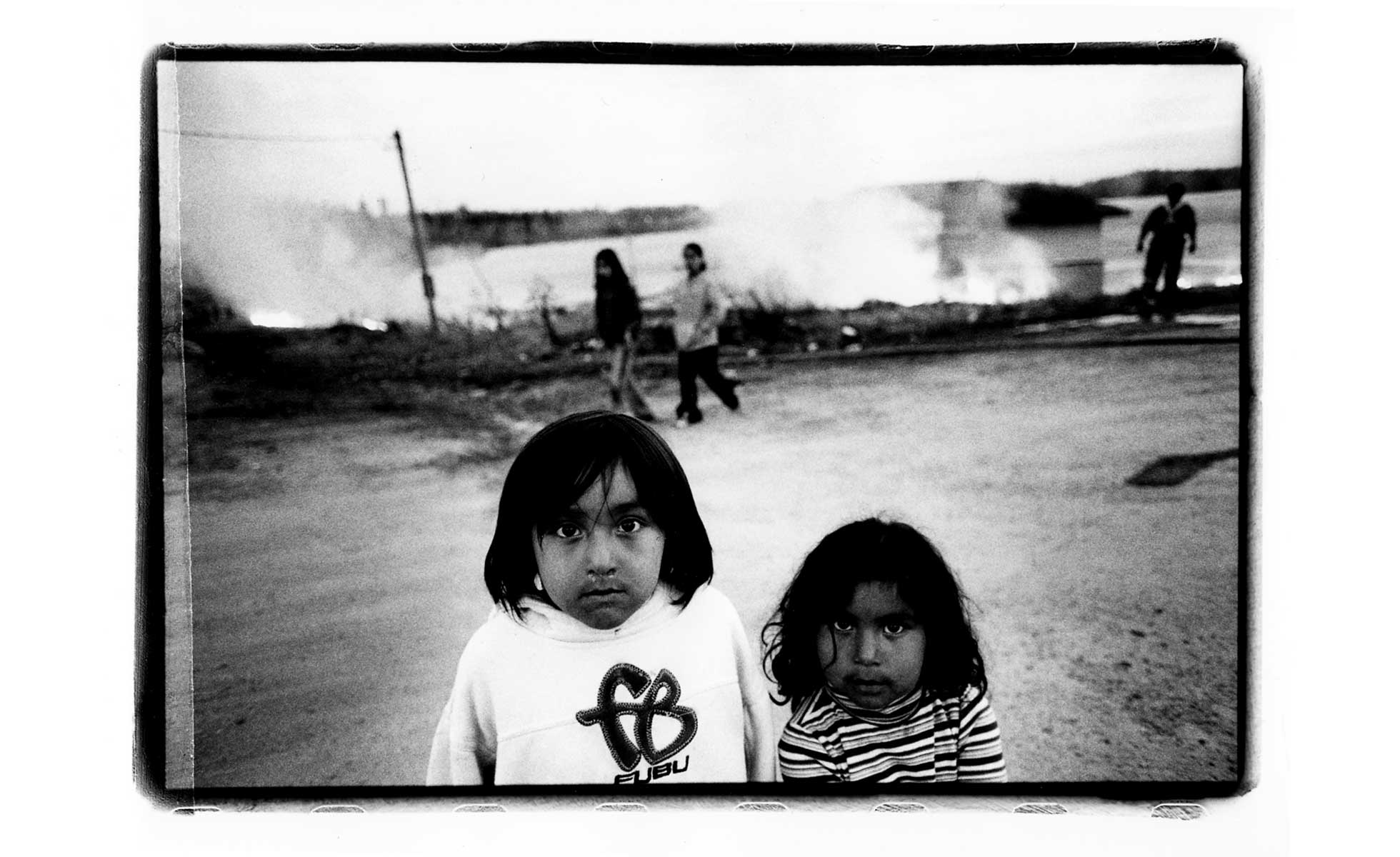

The Wabigoon River has been sacred to the people of Grassy Narrows for generations. Over the years, mercury contamination has triggered an ecological crisis that has devastated the local environment and community members’ health. (Photo: Howl Arts Collective via Flickr)

Biologist Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published in 1962. The book — about widespread agricultural pesticide use and how toxic chemicals like DDT were threatening insects, birds and other wildlife — garnered widespread acclaim and is heralded as a catalyst for the modern environmental movement.

That same year, a pulp and paper mill in Dryden, Ontario, began dumping untreated mercury waste into the Wabigoon River — more than 9,000 kilograms up to 1970. The mill was upstream from several First Nations communities, including Grassy Narrows, home to the Asubpeeschoseewagong Netum Anishinabek people. Mercury contamination has triggered an ecological crisis that has devastated the local environment and community members’ health to this day.

The Wabigoon River has been sacred to the people of Grassy Narrows for generations. Along with the chain of lakes through which it runs, the river provided fish, drinking water and nearly full employment in guiding and commercial fishing. But shortly after the mill started dumping, mercury began appearing at alarming concentrations far downstream and throughout the entire food chain — in the sediment and surface water of lakes and rivers, where bacteria converted it to toxic methylmercury, which accumulated in the tissues of fish, aquatic invertebrates and people.

Silent Spring introduced the concept of bioaccumulation, the increasing concentration of toxic material from one link in a food chain to the next. Scientists who have monitored mercury in Grassy Narrows found the higher up an organism is on the food chain, the more mercury it contains. Top predatory fish, such as northern pike, have more mercury than fish that eat insects, such as whitefish. Grassy Narrows’ residents have elevated levels of mercury in their blood, hair and other tissues from eating fish and other aquatic foods as part of their traditional diet.

Mercury is a potent neurotoxin. Because of chronic mercury exposure, people have suffered from numbness in fingertips and lips, loss of co-ordination, trembling and other neuromuscular problems. Mercury poisoning has also been linked to developmental problems in children, which persist into adulthood.

Japanese researchers, who have monitored the health of Grassy Narrows’ residents since the early 1970s, concluded that many suffer from Minamata disease, named after the Japanese city of Minamata, which was poisoned with mercury when a chemical company dumped tainted wastewater into Minamata Bay in the 1950s and ’60s.

Grassy Narrows is at the centre of one of the worst toxic sites in Canada. Scientists have found dangerously high concentrations of mercury in area lakes more than 50 years after initial contamination. One meal of walleye from nearby Clay Lake, a traditional fishing area, contains up to 150 times the amount of mercury deemed safe by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Because of mercury contamination, the Ontario government closed Grassy Narrows’ commercial fishery in 1970 and told people, particularly children and women of child-bearing age, to avoid eating fish. Though well-intentioned, this policy worsened residents’ health by encouraging them to replace a staple wild protein source with store-bought food, which is inferior in quality and nutritional value.

Fish are a traditional food of Indigenous communities in Northern Ontario, and their harvest and consumption are important for culture and health. Fishing is also a protected treaty right. Years of case law, as well as the Supreme Court of Canada’s 2014 Tsilhqot’in decision, have drawn attention to the fact that treaty and Aboriginal rights enshrined in Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution are meaningless if Indigenous peoples can’t continue to live off healthy populations of wild game, fish and plants.

A recent scientific report found that Grassy Narrows’ Wabigoon River can be cleaned up, and the fish can become safe to eat again — but only with political will.

The underlying message of Silent Spring, that everything is connected, is tragically playing out in Grassy Narrows. The people there have resisted degradation of their lands and waters and are leaders in the environmental justice movement.

It’s time for the provincial and federal governments to join with Grassy Narrows to clean up the Wabigoon River. No single act would go further to illustrate that a new era has dawned in our relationship with Indigenous peoples and our shared environment.