In May 2019, the Blueberry River First Nations court case against the province began: the case focuses on the fact that the cumulative impact of industrial activities has significantly impacted the lands and wildlife within Blueberry’s traditional territory and, accordingly, their treaty rights.

One of the pivotal arguments in the Blueberry First Nations’ case focused on interpretation of what is known as the “take up clause,” which is contained in most numbered treaties.

Treaty 8, for example, states:

And Her Majesty the Queen HEREBY AGREES with the said Indians that they shall have right to pursue their usual vocations of hunting, trapping and fishing throughout the tract surrendered as heretofore described, subject to such regulations as may from time to time be made by the Government of the country, acting under the authority of Her Majesty, and saving and excepting such tracts as may be required or taken up from time to time for settlement, mining, lumbering, trading or other purposes.

Interpretation of what was meant by “from time to time” was a significant component of opening arguments.

During negotiations with the Crown, as records from Crown agents reveal, Blueberry’s ancestors were repeatedly assured that although lands would be taken up from time to time, this would not affect continuance of their mode of life (which depends upon healthy ecosystems to support healthy wildlife populations). Clearly, Blueberry First Nations ancestors negotiating the treaty could not have foreseen the astonishingly high level of industrial disturbance the future would hold: as of 2016, more than three-quarters of their traditional territory was within a few minutes’ walk of an industrial footprint.

It was also unlikely that Crown agents could have contemplated the future scale of industrial activity when they promised that land would only be taken up “from time to time.”

But this is not what the province argued in court. Rather, the province’s lawyer said it was likely apparent when the treaties were signed that there was an awareness that: “The white man is bound to come in and open up the country.”

The province stated that “taking up” from “time to time” could not be clearer in “foreshadowing change.” It argued, “Treaty 8 did not promise continuity of 19th century patterns of land use, as is made clear both by the historical context in which Treaty 8 was conducted and the period of transition it foreshadowed.” Ultimately, the province implied that both sides more or less anticipated and agreed to current levels of industrial activity.

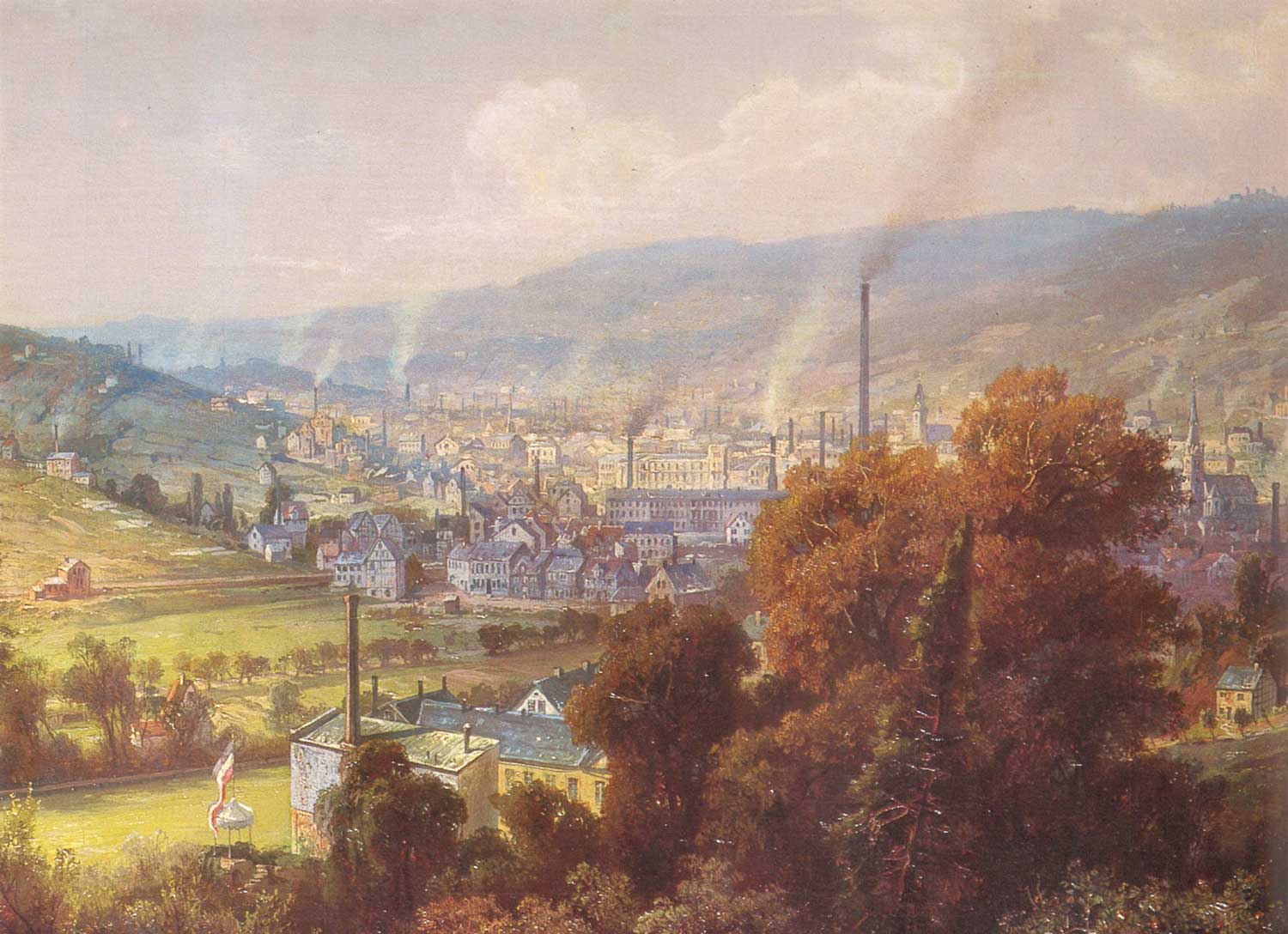

I suppose Crown agents could have had a sense of what was to come. After all, they had just left Europe, which had been transformed by the Industrial Revolution, and were travelling to Canada intending to colonize, the dictionary definition of which is to “come to settle among and establish political control over.”

Industrial europe. (Photo: Atamari via Wikimedia Commons)

One can’t but help think of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, who, having amassed a significant amount of power and capital on this planet, and facing its potential ecological ruin, have set their sights on colonizing the moon and/or Mars.

Sometimes I question why we need a judge to adjudicate on this case for months and months. The Crown said it would take up land from time to time, but instead has taken up most of it. It’s like a neighbour asking to pick tea leaves from time to time in one’s yard and then setting up a Starbucks.

The impacts of the current activity levels are such that, Giltrow, in response to the question of whether or not Blueberry First Nations is still able to hunt and fish, said:

When [Blueberry First Nations members] have available to them only areas in the core of their territory and traplines that are of marginal quality because they are surrounded by Industrial Development, or when they have to go further and further out to find less and less success, or when the animals they kill are not healthy to eat, when members give up, when it becomes so challenging, including economically, to pursue, when the knowledge and skills to carry out the mode of life are no longer transmitted between generations, then the meaning has fallen away from the Treaty right.

The original Indigenous Peoples of this land, who called it home for thousands of years before my ancestors arrived, agreed to share it in return for a promise that their way of life would be protected. As Giltrow outlined, the Indigenous signatories’ consent to settlement of their territory via the treaty was “a large price to pay, and a substantial benefit to the Crown.” As such, according to Giltrow, “Under the Treaty, government has the power to take up land, but also a corresponding duty to protect a way of life.” If we are not of Indigenous descent, then it was on our ancestors’ behalf that a solemn promise was made to Blueberry’s ancestors that their mode of life would continue.

We are all treaty people. Let’s do what we can to uphold our side of the bargain.

This is the second article in a five part series on the legal challenge by Blueberry River First Nations against the Province of B.C. over treaty rights infringement.

Our work

Always grounded in sound evidence, the David Suzuki Foundation empowers people to take action in their communities on the environmental challenges we collectively face.