Extreme flooding events are increasing with climate change. Research shows how clearcut logging increases risks to communities and ecosystems.

B.C.'s Fraser Valley in November 2021. Credit: UBC Applied Science

Clearcut logging can degrade forest ecosystems in Canada and leave communities and ecosystems more exposed and prone to one of climate change’s most catastrophic impacts: extreme flooding. These floods can be triggered by more intense precipitation over longer durations and/or more frequent precipitation events. The potential impacts of floods on people are significant, and likely to get worse.

Forests in Canada can help to mitigate these growing impacts.

Forests, particularly older, more complex forest ecosystems, act as natural “managers” of rainwater and snowmelt, helping to slow the pace of water movement and reduce the risk of extreme flooding events. Their leaves and needles help to decrease the intensity of water hitting the ground. Older trees also usually have larger canopies, which disperse rainfall. Conifer trees, specifically, provide shade during the spring before the rest of the forest “greens up”, which helps to moderate the rate of snowmelt. Older trees and complex forest ecosystems also provide greater soil stability, as tree root networks and other plants provide expansive anchors and absorb water. Even when old trees in a forest eventually die, and no longer mitigate against flooding, they still serve a host of other values.

Forests play a vital role, and left intact, serve as giant sponges, absorbing, storing and then releasing water slowly, providing for year-round moisture, cool micro-climates, and water purification.

Dr. Peter Wood, professor of forestry at UBC

Industrial logging can impair forests’ ability to regulate water movement

British Columbia’s (BC) coastal and inland temperate rainforests are stark examples of how clearcut logging can degrade forest ecosystems’ function by destabilizing rainwater and snowmelt movement through landscapes.

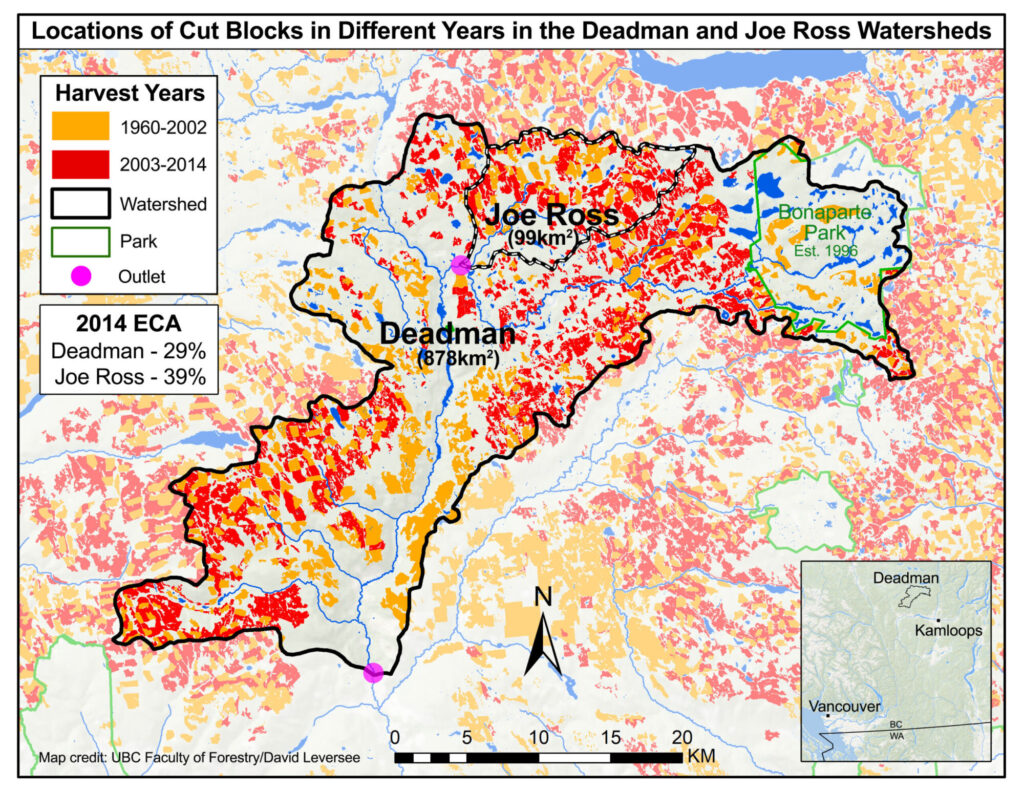

Tree removal reduces a watershed’s ability to moderate the flow of water, and is associated with faster runoff and more frequent surges in water volume. Research in BC’s Interior found that a watershed that had been at least 30 percent clearcut experienced an increase in annual and monthly water yields and annual peak flows (the maximum flow of a stream or river in response to snowmelt and rainfall), as well as an earlier annual peak flow, compared to a similar watershed that had not been logged. Another study found that harvesting influenced small, medium, and very large flood events, and the sensitivity to harvest grew with increasing flood event size and watershed area.

This is especially critical on steep slopes, where gravity is also at play. The hazards of flooding are increasing in BC, where, despite the risk, sloped areas are accessed for wood supply more frequently now than historically, due to the fact that flatter areas have already been logged.

Credit: David Leversee, UBC Faculty of Forestry

The implications of growing flood intensity and frequency are far-reaching. In addition to affecting human lives, extreme flood events can also have significant negative impacts on water bodies–by increasing sediment loads, eroding river banks (which can alter a river’s natural flood mitigation capacity) and initiating algal blooms. One study examining the ecological impact of floods concluded that extreme floods resulted in losses in almost every ecosystem service studied.

In addition to flooding, global studies have illustrated how clearcutting forests can degrade forest structure, leading to more landslides. For example, research in subalpine forests found that five years after logging, root reinforcement had been reduced to 40 percent, and 15 years after logging, there was no remaining reinforcement capacity. In addition, the volume of landslides was four times greater following clearcutting, when compared to unlogged areas, and this persisted for up to 45 years. This reflects the fact that stumps left after logging decay and lose their ability to retain soil, and only slowly re-establish as new trees grow.

Clearcut logging in Caycuse Valley, British Columbia. Credit: TJ Watt

Integrating flood risk into forest management planning

Management of natural resources has a tendency to reduce complex systems to simple and easily quantifiable measurements – what is known as a “reductionist” approach. For example, the UN’s definition of a forest is: “Land spanning more than 0.5 hectares with trees higher than 5 meters and a canopy cover of more than 10 percent.” This also includes younger stands and plantations “which have yet to reach a crown density of 10-30 per cent or tree height of 2-5 metres” and areas “which are temporarily unstocked as a result of human intervention such as harvesting or natural causes but which are expected to revert to forest.” Under this definition, recent clearcuts and second- or even third-growth plantations are considered the same as forests that have never been logged, erasing the unique values of natural, primary and old-growth forests.

A similar issue of oversimplification has historically plagued studies that evaluated the relationship between logging and increased flooding events. While scientists have determined a causal link between logging–especially logging on slopes–and flood events, the historical approach to incorporating flood management into forestry planning has been overly simplistic. As a result, flood projections often haven’t reflected the true risk of flooding after logging, particularly during extreme weather events that are increasing with climate change.

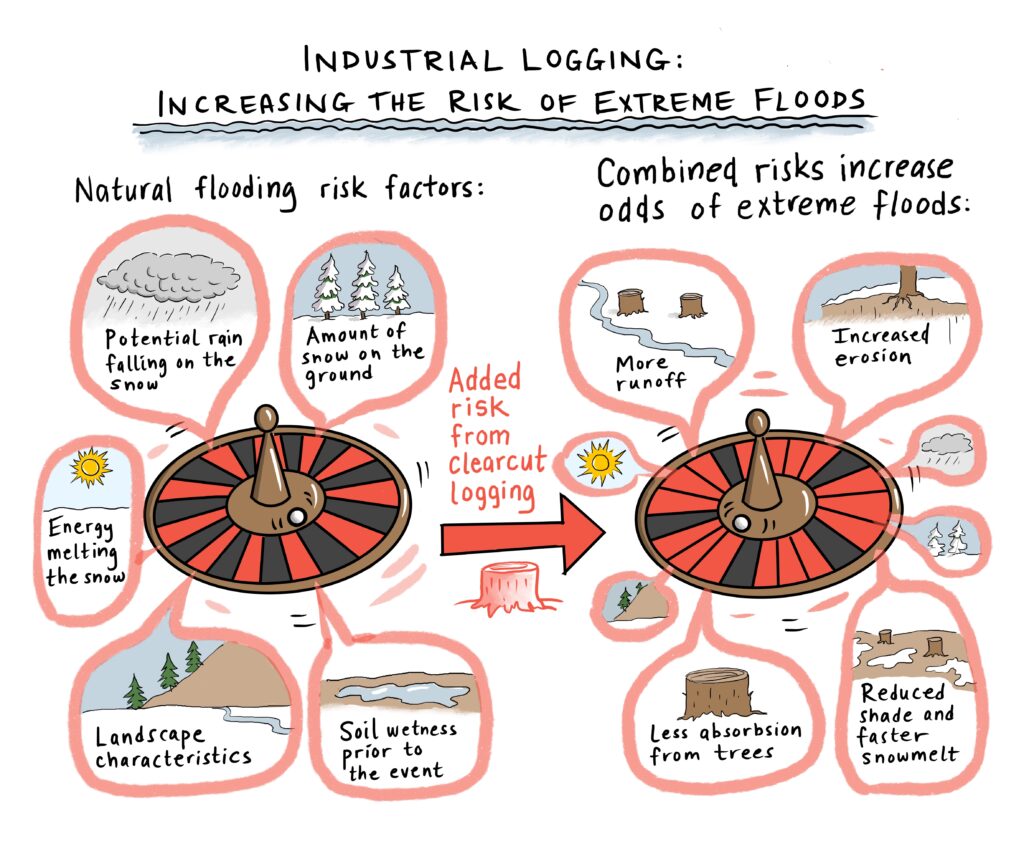

In addition to logging, many other factors affect flooding risk, including soil moisture levels, soil compaction, snow depth, timing of snow melt, slope aspect (i.e., if it’s facing east or west), slope angle, level of rainfall, and more. These factors are considered “chancy” and vary considerably over time and space. As a result, predicting flood events requires a probabilistic approach that takes the stochastic (random) nature of the myriad of contributing factors into account.

When it comes to understanding how logging might increase flood risk, a deterministic approach would look at the logging alone and try to figure out its direct effect. But the risk of flooding is influenced by many things, such as how much snow is on the ground, whether it’s melting or not, how much rain is falling, and the characteristics of the landscape itself. These factors interact over time in complex ways.

Dr. Younes Alila, UBC News

Credit: Courtenay Lewis

As a recent news story covering a local battle over watershed management notes, “[Dr. Younes] Alila says probabilistic modeling takes into account the random nature of the forces influencing flooding — a complex interplay he calls ‘the power of the forest’ — and produces projections about the likely severity and frequency.” His decades of research have shown that conventional scientific methods have underestimated the role of industrial logging in elevating flood risk and have led to forest management policies and practices that “severely and consistently underestimated” the impact of forest cover loss on flood risk.

Working with forests to lower extreme flooding risks

Natural systems are complex and often self-regulating. Human activities that are under our control such as clearcut logging and anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions have fractured these natural regulation mechanisms, putting people and ecosystems at risk. Although we can no longer be sure there is still-frozen ground when the first rainfall comes, we can control where, when and how much forest cover is removed from each watershed by logging. Forest management planning must step up and develop the appropriate risk-based responses, by considering multiple variables, cumulative impacts and the application of a precautionary approach. More robust means for modeling floods and integrating appropriate risk models into forestry planning is needed.

It all starts with a fundamental shift in mindset. Logging practices within the province’s Timber Supply Areas need to be updated in favour of abandoning clear-cut logging for biodiverse-friendly, restorative practices, including selective, strip-cut and small-patch logging. We must synchronize our flood management strategy in the more populated lowlands with our land use, forest resources and water resources management policies in the uplands.

Dr. Younes Alila, professor in the forestry department at the University of British Columbia

A recent analysis has revealed that only three percent of BC’s high-productivity old-growth forests are still intact. Remaining old-growth must be protected and restorative forestry practices must be implemented, including ensuring that forests that have already been degraded by logging are restored and managed to increase resiliency. Most importantly, a “climate risk impact test” should be applied to all forest management decisions, to inform forest managers as to whether a given action will increase the vulnerability of the forest and adjacent ecological and human communities to identified climate change risks, including floods. More sustainable forestry approaches can and should be implemented, including lowering the percentage of each watershed harvested. Forest management can become more holistic, and include increased recognition that some forests should not be logged at all.

Help Canada’s degraded forests!

This blog focuses on the impacts of industrial logging on climate change and extreme flooding in forests. It is part of a joint blog series by the David Suzuki Foundation and the Natural Resources Defense Council exploring forest degradation in Canada.

Our work

Always grounded in sound evidence, the David Suzuki Foundation empowers people to take action in their communities on the environmental challenges we collectively face.