Canada, as a signatory to the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, must halt and reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2030.

(Credit: Jillian Cooper)

If you’ve ever had the privilege of walking through an old-growth forest on the British Columbia coast, you’re probably familiar with the wondrous sight of a tree with root masses that start well above the ground.

These roots tell a story about another tree that reached the end of its life and provided nutrients to a seed that happened to land on its fallen and decaying trunk. The seedling sent out rootlets that traveled into and around the rotting log, eventually connecting with the ground. When the fallen tree finally decomposed completely, the rootlets, which are called “prop roots” once they’re sturdy, curved around the hollow where the old tree used to be, leaving the new tree’s base elevated from the ground. In addition to providing nutrients, these fallen logs give saplings a literal “leg up”, elevating them from competing new growth on the forest floor.

Even outside of these long-lived coastal forests, many of us have witnessed new life sprouting from dead trees. This relationship between new trees and old provides a striking example of a nutrient cycle in action, and of forest dynamics that have evolved over hundreds, if not thousands, of years. The fallen tree that decayed and supported the new growth is known as a “nurse log.” Its role after death helps to illuminate that forests are much more than just living trees.

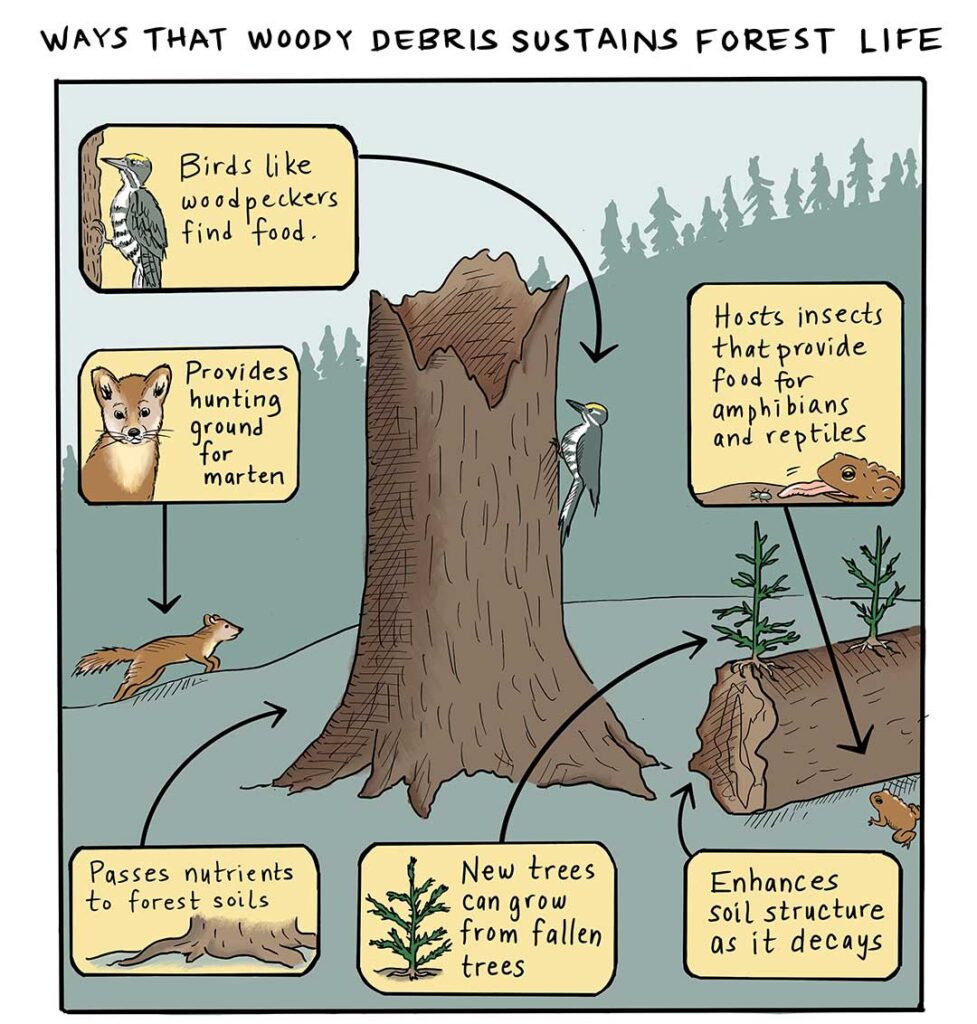

The ecological role of woody debris

Decaying logs, snags (standing dead trees) and stumps are also called coarse woody debris. Many forest organisms depend on this debris for habitat or as a food source. Bacteria, fungi, lichens, mosses, plants, termites, ants, beetles, snails, salamanders, reptiles, birds and mammals use these habitats. Grouse use coarse woody debris for shelter, and American pine marten, an important furbearer in many northern Indigenous cultures, use subnivean habitat – the openings beneath fallen snow when it is supported by woody debris or other structures – to hunt small prey in the winter. Snags feed insects from the inside, which in turn attracts insect-loving species on the outside. Some bird species excavate cavities into the dead trees, which then provide homes for many other species. In the B.C. Interior, about one-third of all forest vertebrates, including woodpeckers and northern flickers, nest in the cavities of dead tree trunks or decaying, living trees. The woody debris also provides nutrients to the soil and forest floor plants.

Natural disturbances vs logging disturbances

Natural disturbances leave distinct types of biological and/or structural legacies. Fires typically produce large quantities of coarse woody debris, as many trees fall and break, but do not fully burn, while other dead trees are left standing. Forests affected by wildfire or insect outbreaks are often characterized by large numbers of snags, while windstorms create uprooted trees.

In comparison, logging often removes much of the debris, both by leveling existing debris and by removing the large, old trees that would otherwise provide for the next generation of woody debris. Research has shown that clearcuts can have less than one-third of the coarse woody debris compared to recent burns and that what remains is primarily in the form of stumps and small logs rather than the snags created by fire.

Many species have declined in abundance after logging because of the net decrease in dead wood left behind in post-logged forests. The loss of subnivean foraging locations is thought to be one of the reasons that marten are negatively affected by clearcutting.

Logging practices have been shown to change forest structure. With some forest management practices, it may be possible to lessen degradation by leaving more woody debris behind, but the application and efficacy of such strategies are quite variable. Setting aside high-integrity forests from logging altogether can be part of a landscape-scale strategy to maintain this forest structure over time and space.

As fires increase due to climate change, increasing efforts will be made to salvage economically viable wood after a forest has burned, so it doesn’t ”go to waste”. But indiscriminate salvage logging reduces the valuable coarse woody debris left by fires and can negatively impact biodiversity in the process. Research has shown that salvage logging can decrease nesting density of cavity-nesting-birds that usually breed in fire-killed trees. Climate change mitigation and adaptation policies for forests in Canada need to be embedded into an overall framework of ecological sustainability that doesn’t further simplify forest structure and the biodiversity it supports. Federal and provincial governments in Canada must set a higher bar for monitoring to assess the extent to which the outcomes of forest management policies are meeting international commitments to halt and reverse land degradation, and push for new strategies where these goals are not being met.

With increasing interest in shipping wood pellets from Canada to international markets, there is increasing pressure to remove wood fibre from our forests, including woody debris. This important forest structure should not be considered waste. It is habitat for many species, including American marten, and critical in maintaining forest biodiversity. Dr. Jay Malcolm, Forestry – Daniels Faculty – University of Toronto

Through science and Indigenous knowledge, we’ve gleaned the rough outlines of nature’s complex systems. Now we need to use our collective intelligence to ensure that how we manage forests is not contributing to further degradation or compromising forest ecosystem recovery.

Help Canada’s degraded forests!

This blog focuses on the impact of industrial logging removing forest debris on forest health. It is part of a joint blog series by the David Suzuki Foundation and NRDC exploring forest degradation in Canada.

Our work

Always grounded in sound evidence, the David Suzuki Foundation empowers people to take action in their communities on the environmental challenges we collectively face.