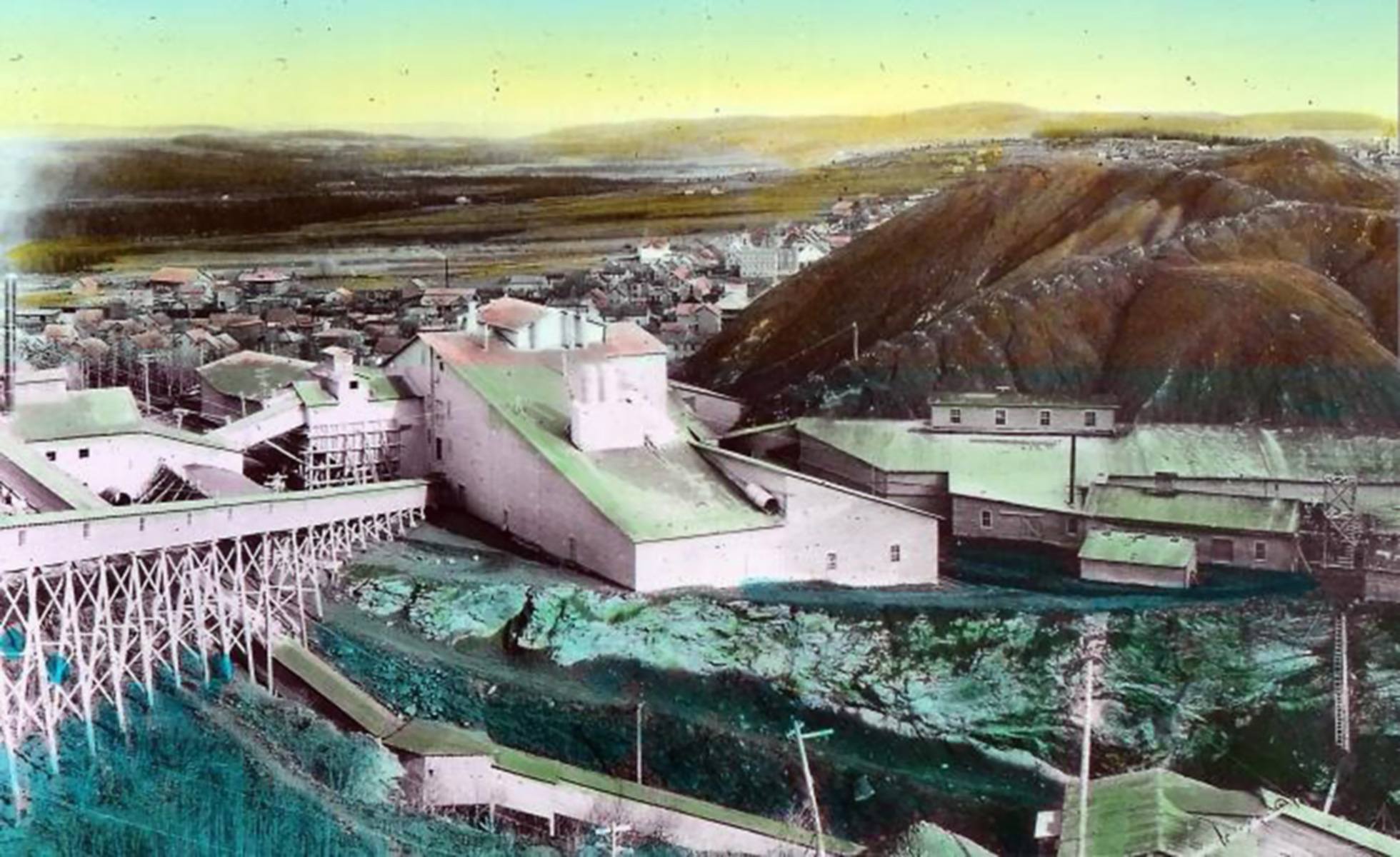

Asbestos mining industry, circa 1923. (Photo: Musée McCord via Wikimedia Commons)

One of the most celebrated films in the history of French-Canadian cinema, Mon oncle Antoine, opens with shots of an asbestos mine in Black Lake (now Thetford Mines) in the 1940s. Beginning in the late 19th century, the Thetford Mines and asbestos regions of Quebec progressed and grew richer thanks to this group of minerals, the health risks of which were little understood at the time. The heat-resistant properties of asbestos made it useful for many industrial applications, including brake pads, handles for pots and pans and residential construction, among others. As the years went by, asbestos was everywhere. It was used domestically and exported. It surrounded us, like a bear hug leading to a slow death.

A whole slice of the history of Quebec and the rest of Canada is framed by the rise and fall of asbestos mining. Today, we know beyond all doubt that this substance is linked to fatal illnesses.

In mid-December 2016, federal Health Minister Jane Philpott spoke in no uncertain terms: “Breathing in airborne asbestos fibres can cause serious health problems, including lung cancer. Exposure to asbestos can also lead to mesothelioma, a rare but aggressive form of cancer with a poor prognosis.”

Exposure over many years by asbestos industry workers and family members who were indirectly exposed at home, as well as the larger population, has left us with a painful heritage that we will regret for a long time. In early 2016, a Canadian Press report painted a grim picture of mortality, both in the past and to come, caused by asbestos exposure: “In 2012, there were 560 new cases of mesothelioma, up from 276 cases recorded in 1992, the Statscan website shows. Between 2000 and 2012…deaths from the asbestos-related malignancy jumped 60 per cent — to 467 from 292.”

The World Health Organization has been warning of this product’s dangers for 30 years. Seen in that light, the recent decision by the federal government to ban the use, import and export of asbestos by 2018 is long overdue.

That decision is a step in the right direction, and one that several health specialists and environmental groups — the David Suzuki Foundation among them — have been demanding for a long time.

In September 2012, David Suzuki Foundation Quebec director Karel Mayrand wrote, “We still have a long way to go to make sure asbestos stays in the ground and no longer poses a threat to human health. Remember, asbestos kills 90,000 people in the world every year: that’s the equivalent of one Hiroshima per year, for generations. The death toll must be stopped. Quebec and Ottawa must act to ban the extraction and exporting of asbestos.”

Petitions were circulated, and voices were raised — including yours. You have spoken out against this industry that has been slowly killing us, and now you have won.

Asbestos will still be present in many buildings, infrastructure and products, posing a variety of challenges for property managers, among others, who must take inventory of and secure, at considerable expense, even the slightest repair job in an affected area. To simply drive a nail into an office wall to hang a picture, if the gypsum board is contaminated, a workplace health and safety team must be called in! Decontaminating sites will take a long time, and will cost a lot of money. But it is the right thing to do and it must be done. Unfortunately, asbestos will continue to be mined in countries that have decided to ignore science and put profits before lives. Russia, for example, has taken over from Canada as a leading irresponsible exploiter of the resource. On a global level, the battle against asbestos is far from over.

Here at the Foundation, our thoughts and our voices of solidarity are with the victims, both past and future, and their families.

To all of you, this is our pledge: We will continue our fight to ensure that science and the precautionary principle light our way, serving as the sole foundation for decisions that affect the environment and indeed our very existence.