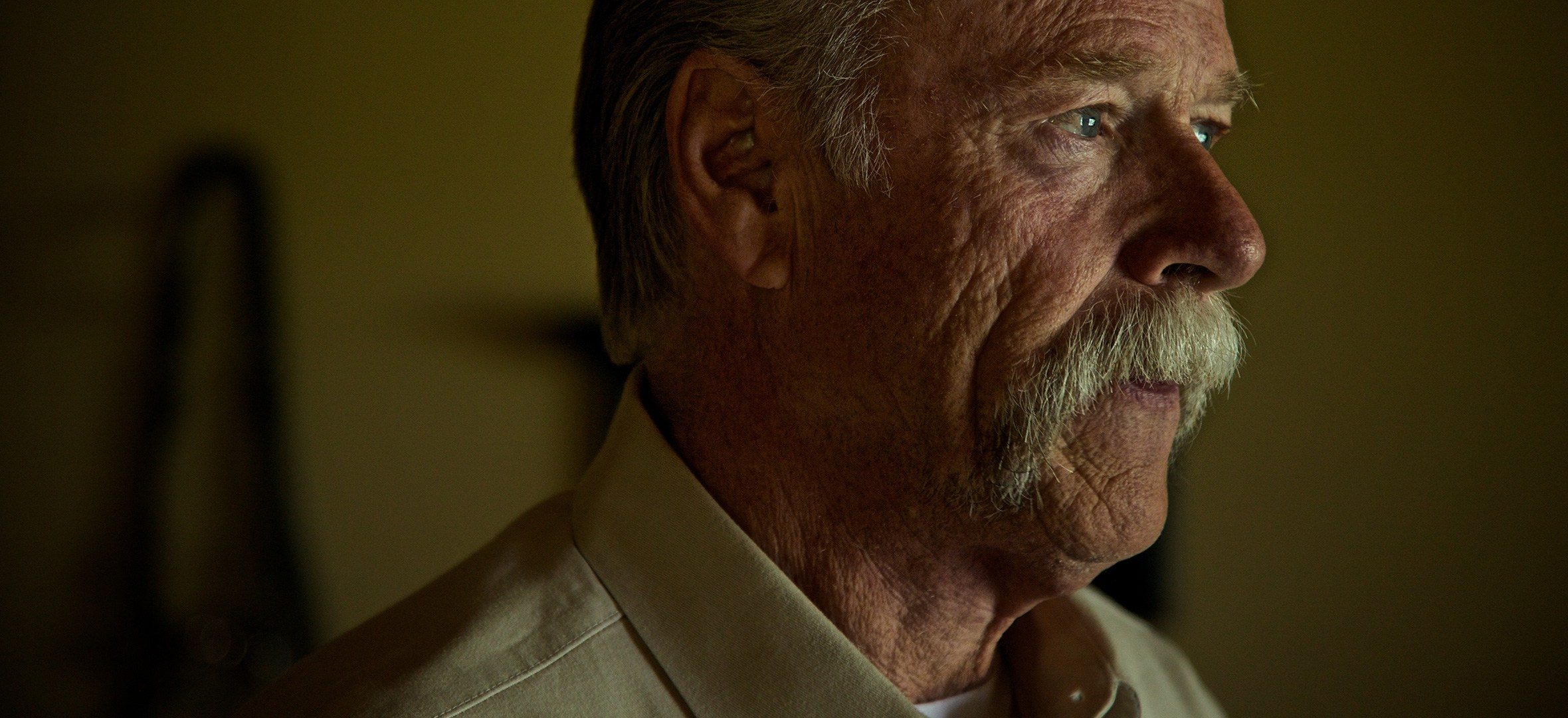

After working around the world as an oil and gas engineer for more than 30 years, Dan Thomas knows a thing or two about the petroleum industry. His home in the Lochend area of Cochrane, Alberta, overlooks large cattle-ranching operations, small acreages, the distant Rocky Mountains and, in just the past three years, over 100 oil well sites.

Dan and his wife, Elaine, planned a quiet, country retirement after returning from the Netherlands, in a modest home connected to a small meeting space to rent out for business team-building retreats and meetings. But a drilling rig appeared 400 metres from the property just days before construction was slated to begin. “If I had had two weeks’ notice, I wouldn’t be sitting here,” Thomas says.

If I had had two weeks’ notice, I wouldn’t be sitting here.

Things changed fast. The area went from one oil rig to 110 in three years, without stakeholder engagement or risk assessments.

An expert in the field, Thomas understands the processes. Modern, high-pressure hydraulic fracturing differs from technology used since the 1950s in one major way: pressure. Conventional fracking used water, chemicals and sand pressurized to about 700 pounds per square inch. Today, upwards of 4.5 million litres of fracking fluid and over 200,000 tonnes of sand can be pumped underground — all at pressures well over 10,000 psi.

During the drilling process, the pressurized chemical mixture (known as “slickwater”) causes rock formations deep underground to fracture and open into fissures. Some injected chemicals travel back up, along with naturally occurring ones like benzene and ethylene. The unwanted, chemically laden water and the desirable oil or gas are supposed to be separated. But there are multiple opportunities for failure and release of hazardous materials, Thomas points out, including broken concrete well seals, improper handling and disposal of flow-back water and burning highly carcinogenic compounds.

Dan Thomas on modern fracking

Oil engineer Dan Thomas speaks about modern high-pressure hydraulic facturing.

Thomas is deeply concerned, given the proliferation of countless local oil and gas developments by small- and medium-sized companies — some without any track record — on top of what he describes as a weak regulatory framework. For example, Alberta’s provincial regulations are supposed to limit the length of time wells can flare, but Thomas recounts some continuously lit for more than two years.

“There was enough flaring going on within this hundred-square-kilometre area to heat 65,000 homes in Calgary on a minus-30 day. It was insanity. And the industry just does not know what’s coming out of the tops of those flares.”

Loss of livelihood, sickness and death

Canada lacks environmental protections enjoyed by similar nations around the world. We’re at or near the bottom in many rankings of wealthy, industrialized countries, placing 24th out of 25 on environmental performance indicators in a recent survey of Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

Without baseline information on air- and water-quality impacts of oil and gas generally and fracking specifically, it’s difficult to quantify exactly what’s happening. But health impacts described by Cochrane-area residents like the Thomases and their neighbours, the Hawkwoods, immediately after the huge increase in local oil and gas production can’t be discounted.

“About three years ago, I started losing my hair,” Nielle Hawkwood says. “And we found out afterward that many women in our neighbourhood, and young girls as well, were losing their hair.”

About three years ago, I started losing my hair. And we found out afterward that many women in our neighbourhood, and young girls as well, were losing their hair.

Nielle Hawkwood sits next to her husband, Howard, on their plush living room sofa. The inside of their farmhouse is warm with the colour of wood. Howard and Nielle are cattle ranchers with a herd of almost 200. Both were born in the Calgary area and have lived together on their ranch since 1980.

The couple finish each other’s sentences as they describe the rapid changes they’ve seen in the past few years. In addition to Nielle’s hair loss, they began noticing drastic changes in their livestock. Three years ago, fertility rates started dropping and more cows than normal were not getting pregnant.

“Two years ago we started having cows that started to die, but we didn’t really think too much of it,” remarks Howard. “And then last year we lost 10 per cent of our cow herd.”

Normally, losses would average one or two cows a year.

Impacts on livestock

They then began to notice dead spots in the grass where cows had urinated.

Soil samples showed higher levels of strontium, a naturally occurring element usually trapped deep underground, elevated levels of chlorine and hydrochloric acid, commonly used in the fracking process — the first clue that fracking may have contaminated their groundwater.

The second clue was the sudden absence of algae, pointing to the presence of biocides often used in fracking fluids. The cows’ water is kept heated throughout the winter, providing an ideal environment for algae to grow — from time to time Howard had to remove the green muck from the troughs. “Last year he didn’t have to clean it out because the water was crystal clear. The algae were all dead,” Nielle notes.

Howard and Nielle say that their problems are not unique. But neighbours won’t speak out for fear their purebred animal or seed stock businesses will be perceived as tainted. The Hawkwoods’ outspokenness has already caused tensions with some of them.

They feel that we’re against them, and they won’t even talk to us in public. They actually walk on the other side of the street.

“They feel that we’re against them, and they won’t even talk to us in public. They actually walk on the other side of the street.”

Many people have quietly left the community, but word’s getting out about the problems, making it almost impossible for those left behind to sell their properties and move away.

The time is fast approaching when the Hawkwoods will have to make a decision. As grass starts to grow back after winter, patches of barren land are clearly more widespread than last year. Howard estimates they lost between one and two acres of productive land in each of the last two years.

“Now if this keeps up, I would imagine that within about 10 years, my ranch will not exist anymore,” he says.

The couple figures they’ll know whether they have to move or not by fall. In the meantime, they lament the gold rush attitude that’s led to the rapid development around the land they’ve called home for so long, jeopardizing Alberta’s role as Canada’s breadbasket.

“What’s going to be left of the agricultural industry if fracking proliferates as it looks like it is?” Howard wonders. “We can’t afford to squeeze it all out at the cost of our environment and our children’s future.””

Others in the community agree.

A parent’s worst nightmare

Half an hour from the Hawkwoods, Chelan Haynes has spent quite a bit of time in the last four years thinking about her children’s future.

“What bothers me is when you walk out into your yard now and you look at the sky and you breathe the air and, you know, it’s a burden to think that this beautiful atmosphere, with the rain falling down, could be contaminated.”

…it’s a burden to think that this beautiful atmosphere, with the rain falling down, could be contaminated.

Haynes couldn’t make sense of it. Her kids were always healthy and strong, running around outside. Like most conscientious moms, she paid close attention to everything they ate and what came inside her home. She was positive nothing she did caused her younger daughter to get sick.

At first, the seven-year-old had trouble walking up the driveway. Then she stopped riding her bike and had to quit her pony riding lessons. After an alarming rash developed on her face, the little girl was rushed to Calgary’s Children’s Hospital. Within hours the diagnosis was confirmed: acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Doctors said the cancer had progressed so far that she may have only lived another month or two without treatment.

Like others in the area who noticed adverse reactions, illnesses and changes to their land and animals since the modern oil and gas industry arrived in Cochrane, Haynes can’t conclusively link fracking to her daughter’s illness. Still, with benzene a common by-product of flaring and a known risk factor for her daughter’s type of cancer, she wishes better monitoring could provide some answers.

“Industry will do the bare minimum. Government will do the bare minimum. I think it’s up to us to demand more.”

Like many of her neighbours, Haynes isn’t opposed to oil development. She recognizes the benefits that come from the industry. At the same time, she acknowledges there’s a larger question to be asked about how the economy and the environment are related.

“If we don’t value our pure air until it’s contaminated, if we don’t value our water and pristine state until it’s contaminated, then our economic system is completely wrong.”

While she has no immediate plans to move, and her daughter is back to being an active little girl, Haynes can’t help but pause whenever she finds herself outside looking at the clouds and the blue sky and tries to notice which direction the winds are blowing.

“Ignorance was bliss but now I know how many sites are in that direction. I know how many are north of us, how many are west. I wonder whether they’re flaring right now.”

Industry will do the bare minimum. Government will do the bare minimum. I think it’s up to us to demand more.

Building the legal case: Breaking ground to protect nature

As a University of Alberta law student in the late 1960s, David Estrin wanted to do something not many others did: become an environmental lawyer. He had been a Boy Scout and connected with nature at a young age. He remembers seeing an ad on a baseball field fence that read “Look up above you and you will see the cleanest sky in the world thanks to natural gas.”

“I remember looking up and, by God, the sky was beautifully blue, vividly blue!”

Because his natural resources law professor’s focus on oil and gas held little appeal, Estrin decided to write his final paper on whether common law water rights existed in Alberta. His research turned up one of Canada’s seminal environmental cases. In 1928, Groat v. Edmonton said the City of Edmonton violated a farmer’s water rights by discharging sewage into a stream used for drinking and watering livestock.

“I thought it was rather inspiring that somebody went to the Supreme Court of Canada and was vindicated in their environmental rights back in 1928.”

After finishing school, Estrin moved to Toronto. Smog blanketed the city. “I remembered that ad on the fence from the baseball park in Edmonton and thought maybe some other people would like to do something about environmental rights.”

He started making calls, found a small group of other like-minded lawyers — the genesis of the Canadian Environmental Law Association — left his position at a legal practice specializing in civil rights and labour law and became CELA’s first and only staff lawyer. “I went from $10,000 a year as a first-year lawyer to $5,000 a year!” he says, laughing. It wasn’t long before he was getting calls to work on pivotal environmental cases.

The early days of environmental law

David Estrin describes the early days of environmental law in Canada.

…if the Alberta government wasn’t going to take this matter seriously, why should Suncor?

In 1983, oil started leaking into the Athabasca River from a Suncor refinery. The pollution travelled downstream, killing fish the Fort McKay First Nation relied on. They laid private charges against the company. This so embarrassed the Alberta government that it decided to take over the case. The only problems: the government had never tried an environmental case before and the prosecutor assigned to the case had only limited traffic court experience.

“The prosecutor they appointed had a nervous breakdown… (and) hid in his hotel room. They had to adjourn the trial,” recalls Estrin, who received a call afterwards asking him to assist with the case. After a hard courtroom battle, the presiding judge found Suncor guilty and levied a paltry $6,000 fine. The judge explained his decision by saying that if the Alberta government wasn’t going to take this matter seriously, why should Suncor?

The judgement on the highly publicized case was seen as damning the government, which quickly asked Estrin to help bolster its capacity to prosecute future environmental cases. Full-time prosecutors — who actually knew how to lay charges and litigate successfully — would soon join Alberta Environment.

“You have to understand that there was no concept of enforcement. Indeed, ministries of environment were generally afraid to enforce. They had no experience in it. They were basically staffed by engineers.”

There’s nothing that requires them to do a damn thing. There are no duties to protect the environment, there are no duties to use their powers, there’s no duty to enforce.

CELA started banging on doors, writing briefs and showing that a lot more could be done. Things began to shift.

But change came slowly, thanks in large part to organizations like CELA, which today boasts more than 20 staff and advisers working on some of the country’s most complex legal cases.

Many of the statutes that came into force seemed more like lip service to the concept of environmental issues than substantive progress, Estrin notes. Many, for example, outlined how the minister responsible may take action.

“There’s nothing that requires them to do a damn thing. There are no duties to protect the environment, there are no duties to use their powers, there’s no duty to enforce.”

Persistence in the face of ridicule

David Estrin and John Swaigen are both founders of Canadian environmental law. Swaigen is a senior staff member at Ecojustice, an organization that, since 1990, has been involved in almost every significant piece of environmental litigation in the country.

From his part-time desk in the Toronto office, Swaigen recalls a more modest beginning. “Basically I wanted to save the world.” Like Estrin, he found his passion was still considered a backwater.

When the Chief Justice of Ontario visited Osgoode Hall Law School, “He told the group that if they went to article at the Ministry of the Environment, they’d be learning from second-rate lawyers.”

You’ll never be heard from again if you do that.

Undeterred, Swaigen eventually heard of a small specialty University of Toronto legal aid clinic that dealt with environmental cases, which would later became CELA. Swaigen articled there under Estrin. When he told his university supervisor he’d decided to join CELA, the supervisor responded, “You’ll never be heard from again if you do that.”

Radicals

At CELA, Estrin and Swaigen became Canada’s first two full-time environmental lawyers. One of Swaigen’s first tasks was editing what amounted to a citizens’ guide to environmental law. The final chapter of the book — focused on Ontario — was on a provincial environmental bill of rights. The topic piqued then Ontario Liberal leader Stuart Smith’s interest. In his 1976 leadership race, he’d pledged to work on environmental health issues.

Smith approached CELA to ghostwrite an environmental bill of rights for the party and introduced it, unsuccessfully, several times. CELA helped draft the bill, which didn’t contain any substantive rights. “It contained a lot of procedural improvements which are important and worthwhile,” Swaigen says, “but the Liberal caucus wasn’t prepared to go so far as to espouse a substantive right to environmental quality.”

By 1985, Swaigen had joined the Ontario Environment Ministry and was trying to promote the idea of environmental rights from within. His approach was to propose individual pieces of an environmental bill of rights separately, hoping they’d be seen as relatively straightforward issues. It didn’t work. “Word came back from the deputy minister that the things I thought were relatively simple to introduce weren’t all that simple.”

While unsuccessful at passing reform from within the bureaucracy, the ministry wasn’t the backwater described.

“The Ontario Environment Ministry had very good lawyers and was not afraid to prosecute. If they lost, they weren’t afraid to appeal it all the way up the Supreme Court of Canada if necessary.”

Canada’s political disconnect

If passing provincial environmental rights legislation was difficult, it may well have been impossible at the federal level — not to mention a potential source of ridicule for anyone who tried.

“Far out would be a fair description, yeah,” former B.C. Member of Parliament Svend Robinson says with a laugh. “Wacko would be another.”

Robinson’s original plans never included electoral politics. When he entered post-secondary school, he’d planned to become a doctor, taking all the required sciences and even finishing pre-med. But he was introduced to student politics at the University of British Columbia and got hooked. Upon graduating, he made a last-minute change and enrolled in law at the London School of Economics.

After finishing at LSE, 27-year-old Robinson returned home and was quickly elected MP for the riding that would become Burnaby-Douglas. “I was a kid when I was first elected!” Despite his youth, he quickly won respect within his New Democratic Party caucus and across the aisle and, by 1980, was his party’s senior spokesperson on justice.

Canada was still feeling the impacts of the 1979 oil crisis, manufacturing job losses and our weak dollar’s negative effect on U.S. imports. On top of that, the country also faced its first test of unity from Quebec’s sovereignty referendum.

So it was no surprise that economic and confederation issues were top of mind for then Liberal Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

Immediately following the referendum, Trudeau initiated the patriation of Canada’s Constitution, including a plan for an entrenched Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In October 1980, a Special Joint Committee of the House of Commons and the Senate was announced, to consult with Canadians about the process. They heard more than 250 hours of presentations over three months — all televised for the first time.

Robinson viewed the process as a kind of nation-building exercise.

I think it was profoundly important for us as Canadians to, for the first time, be debating our own constitution.

“I think it was profoundly important for us as Canadians to, for the first time, be debating our own constitution.”

Then NDP leader Ed Broadbent asked Robinson to be one of the party’s two Joint Committee members. He took to it “like a duck to water.” But Robinson quickly decided the Charter had to be more than just traditional civil and political rights. For him, it was a statement of Canada’s most fundamental values and core principles and defined what this country was all about.

Drawing inspiration from the UN’s International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Robinson went about crafting an amendment to include the environment as a fundamental Canadian right. “That was just an essential part for me of what it means to be Canadian and had to be included in the Charter .”

Apple pie

But not everyone saw it that way.

On January 1, 1981, after Robinson’s impassioned argument in front of the Committee, then Liberal Justice Minister Jean Chrétien stood up and called the proposal “high-sounding rhetoric.”

“I am waiting soon for an amendment to inscribe in the Constitution the apple pie and the recipe of ma tante Berthe, and I do think that we cannot put everything there,” he thundered.

Shocked, Robinson responded, “I suggest it is inappropriate to equate the recipe for apple pie, for example, with the right to a clean and healthy environment.”

The motion was defeated 22-2.

Despite hard work and strong statements in the House, Robinson never thought his amendment would pass.

“I think people just didn’t make the connection between the Charter of Rights and the environment — that connection just wasn’t made.”

Still, for Robinson, the idea of environmental rights remains fundamentally connected to the Charter as it exists today.

“We included aboriginal rights in the Constitution as an essential element and rightfully so. But if the water that First Nations people drink is polluted, if their land and their water is being destroyed, then those aboriginal rights that are in the Charter of Rights become fundamentally weakened.”

A special relationship with the land

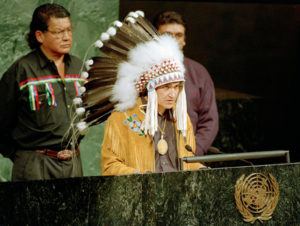

Ovide Mercredi, a member of the Misipawistik Cree Nation and former Assembly of First Nations national chief, was born in 1946 in Grand Rapids, Manitoba, a remote northern community on the shore of Lake Winnipeg.

“I grew up at a time when the Earth was unspoiled in our territory. I could drink the water from the Saskatchewan River.”

In 1946, Grand Rapids had no road access and Mercredi’s people were still living as trappers, fishers and hunters — a completely different way of life than non-aboriginal Canadians. For Mercredi, the dominant society’s preoccupation with concepts like the economy comes at great expense.

What I hear from them is always to talk about how important it is to create jobs, and somehow that becomes the license for destroying everything else around us.

“What I hear from them is always to talk about how important it is to create jobs, and somehow that becomes the licence for destroying everything else around us.”

Mercredi saw economic preoccupation as a root cause of his people’s suffering, which spurred him to pursue a political career. He was elected AFN chief in 1991 and, during his first term, led the negotiations for First Nations during the Charlottetown accord deliberations — the second attempt by the Brian Mulroney government to renegotiate the Constitution.

Like most aboriginal people in Canada, Mercredi had an inherent mistrust of government dealings.

Before Canada existed, the relationship between aboriginal peoples and settlers was managed by the British Crown. It was cemented with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, described by some as a “Bill of Rights” for Canada’s indigenous population. King George III wanted to both avoid the protracted conflicts that characterized previous North American colonization and pave the way for British settlers following the Seven Years’ War.

The Proclamation’s sections dealing with aboriginal relations admitted “great frauds and abuses” had been committed against the first peoples in Canada and sought a new relationship. The document outlined boundaries beyond which land was considered unceded — essentially off limits to new arrivals. It also ensured all future land negotiations would be made in public and recorded with treaties.

As long as the sun rises and the river flows

While Canada’s relationship with aboriginal peoples remained tenuous, the Crown was a symbol of the promise made to achieve a nation-to-nation relationship.

In 1969, when Prime Minister Trudeau and then Minister of Indian Affairs Jean Chrétien introduced the White Papers proposal to end the special status of First Nations in Canada, the reaction was swift and fierce. Aboriginal peoples across the country stood up and demanded the bill be withdrawn, saying it ignored their inherent rights and flew in the face of past commitments like the Royal Proclamation. Trudeau listened and, in 1971, promised to drop the proposals.

But the well was poisoned. Many First Nations saw Trudeau’s sweeping plan to repatriate the Canadian Constitution as an attack on their status.

Assembly of First Nations Chief Ovide Mercredi at the December 10, 1992 ceremony marking the start of the International Year of the World’s Indigenous People (UN photo Eskinder Debebe)

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Minister of Justice Jean Chrétien at the constitutional conference. (Photo: Library and Archives Canada)

Queen Elizabeth and Prime Minister Trudeau at the Constitution signing. (Photo: Library and Archives Canada)

Mercredi recalls the fear about severing the connection between Canada and the British Crown. “This would be another way in which there would be the extinguishment of treaty and aboriginal rights in Canada.” A group of First Nations leaders travelled to London, England, to petition the government there to block patriation. British Privy Council Judge Lord Denning ruled against them but was careful to reaffirm the special relationship they had with the Crown.

In his judgment, Denning clearly stated that the British Crown’s historical responsibility to First Nations would continue to apply to Canada “so long as the sun rises and the river flows.”

Mercredi saw the Charlottetown negotiations as a means of enshrining a deeper understanding of aboriginal values and teachings in the highest law in the land. But, just like Mulroney’s first attempt with the Meech Lake Accord — and Svend Robinson’s original attempts before that — Charlottetown ultimately failed. On October 26, 1992, the country voted 54.3 per cent to 45.7 per cent against the accord. The Globe and Mail proclaimed, “Canada’s people have put an end to constitution making by the politicians.”

The loss crushed Mercredi’s dream to enable First Nations to make their own laws and govern their own territories. “This would have allowed us to wrap ourselves in a constitutional blanket so we would heal and develop and get stronger.”

These failures would reverberate for years. For First Nations, they confirmed the idea that mainstream Canadian values were almost diametrically opposed. They led to another Quebec sovereignty debate, nearly tearing the country apart. And they left most Canadians feeling substantive changes to the Constitution were impossible.

The country Canada could have become

It’s hard to imagine Canada’s constitutional wrangling making any headlines at all in the rest of the world. They certainly didn’t make waves across the Atlantic in Norway, where less than six months prior to Canada’s vote on the Charlottetown Accord, the country’s legislature, the Stortinget, unanimously passed an amendment to the Constitution that included:

“Every person has a right to an environment that is conducive to health and to a natural environment whose productivity and diversity are maintained.”

Far from window dressing, this amendment guaranteed all Norwegians the right to a healthy environment both procedurally and substantively, providing for environmental rights with regards to health, the preservation of diversity, intergenerational equity and the right to be informed of environmental issues.

Norway and Canada share a number of similarities. Both are northern, oil-producing nations, considered socially progressive. But the comparison ends there. While Norway amassed more than $900 billion in oil royalties and taxes into a sovereign wealth fund designed to maximize the benefit of these windfall profits for generations to come, Alberta has saved only $17 billion, despite having a 20-year head start.

For Mitch Anderson, the comparison is even more fascinating because many policies for which Norway is celebrated started in Canada.

Norway is the country that Canada could have become.

“Norway is the country that Canada could have become.”

Anderson, a Vancouver-based freelance writer, began to see the issue of the Canadian oil and gas industry almost completely reframed as a money-and-jobs conversation instead of a discussion about the ecological impacts after working eight years as a staff scientist at the Sierra Legal Defence Fund. He saw this as an opportunity, not a deterrent.

“If we are being led to believe that the fossil fuel industry is so critical to Canada’s economy then why don’t we look at other jurisdictions that are reliant on the fossil fuel sector and see some of the choices they made?”

He started taking a closer look at Norway.

The Statfjord oil field in the North Sea. (Photo: flickr user oter)

The interior of Norway's parliament, the Stortinget. (Photo: flickr user stortinget)

The Alberta oil industry pioneered processes, technology and government management. In 1976, Alberta Premier Peter Lougheed created one of the world’s first sovereign wealth funds, the Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund, set up to receive 30 per cent of all non-renewable-resource revenue. At its peak value in 1987, the fund was worth $12.7 billion (over $24 billion in 2014 dollars).

But that same year, an economic downturn prompted the government to stop contributing and start withdrawing money, a trend that lasted until 2006. After almost 20 years of drawing revenue, the government resumed small contributions, but those stopped in 2008-09 and haven’t been resumed since. The latest reports show the fund sits at $17.3 billion, a net loss of almost $7 billion compared to 1987.

Norway, by comparison, made Lougheed’s idea nearly bulletproof. Their fund, started in 1990, is an arm’s-length institution that can’t become a major factor in political decision-making. Since then, at least 96 per cent of oil revenues have been deposited into the fund — including a hefty 80 per cent tax on oil company profits — growing it to over $900 billion.

According to Anderson, Norway’s largely depoliticized oil wealth means policies are clearer and more forward-thinking.

“Norway has some of the most expensive retail gas prices in the world, but there is support for that because people recognize there are externalized costs from burning fossil fuels.”

Attention paid to environmental costs of fossil fuel extraction put the spotlight on Norway’s industries overseas. While the country boasts one of the world’s strongest domestic programs to tackle climate change and protect ecological sustainability, outside of Norway this is not always the case.

“One of their biggest environmental controversies isn’t actually about Norway,” Anderson says. “It’s about Statoil investing in the Alberta oil sands, which is considered very unethical by many Norwegians.”

Foreign businesses drop their standards to meet ours

Back in Cochrane, retired oil engineer Dan Thomas has high praise for Norway’s state-owned Statoil. But he laments lax regulations that allow companies like Statoil to be held to a much lower standard when doing business in Canada.

“They come over here to Canada and they’re no better than we are.”

As an insider, he’s well-placed to compare what’s happening to other parts of the world. He describes weak governance falling further behind every day.

Alberta never had a good regulatory process but we gutted it over the last 10 years just for the purposes of cutting costs.

“Alberta never had a good regulatory process but we gutted it over the last 10 years just for the purposes of cutting costs.”

He blames the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, which, he says, is driven only by reducing costs, regulations and royalties. Thomas draws comparisons between CAPP and the broader attack on science underway inside government, noting that if we don’t understand the science we won’t understand the longer-term implications of decisions that are solely economically driven. “It’s short-term thinking driven by dysfunctional economic models.”

Thomas points to Norway and elsewhere as examples of how stronger environmental regulations can actually lead to better economic outcomes. “They make more over the long term, to tell you the truth,” he says.

Down the road from Thomas, retired dentist Gary Tresidder recalls trying his best to resist the wave of oil development that swept through the Cochrane area.

“They tried to put an oil well on the property and I wouldn’t let them. I told them I’d hold them up as long as I could. So they went across the fence and they just drilled underneath me.”

Lured by the fresh air and stunning landscape, Tresidder moved to Cochrane from his Ottawa hometown almost immediately after finishing university. Like others in the area, he didn’t know anything had changed until his family and neighbours — especially women — started to suffer similar symptoms: chronic coughing, skin irritation, itchy eyes and hair loss. When the wells started to show up, residents began putting two and two together.

She started to have massive migraines. She was getting stomach aches, cramps, she had no energy, she couldn’t get out of bed…

Tresidder’s home sits directly in the path of prevailing winds coming across Dan Thomas’s acreage through a cluster of well sites. Upwind from him, several of these wells flared continuously for a period of 18 consecutive months, releasing colourless and odourless gasses.

“I was developing a chronic cough that lasted for the whole 18 months that they flared those nine to 10 wells.”

He also had trouble focusing and remembering names and other details. He decided to escape to Phoenix, Arizona, where his symptoms cleared up within a few days. They came back when he returned.

“It was like I was on a drug or something. I was almost scared to drive because of it.”

Like Chelan Haynes, the worst was seeing his younger daughter fall ill.

“She started to have massive migraines. She was getting stomach aches, cramps, she had no energy, she couldn’t get out of bed… She missed 58 days of school that year when they were flaring eight to ten wells constantly.”

Without baseline data and stronger monitoring programs, Tresidder can’t prove his family’s problems are directly caused by oil and gas developments. And he maintains he has no problem with the oil industry in general, just the newer technology of high-pressure horizontal hydraulic fracturing. “They had no idea what they were doing. Not a clue.”

Tresidder confronted chemical engineers working for Alberta’s industry-funded regulator and those employed by the oil companies about underground reactions. He asked whether they know how these new compounds react during the flaring process.

“Two hundred to 2,000 chemical reactions that occur underneath the ground and they can’t name me two.”

Everyone is getting sick and no one is helping

The pressure Tresidder and his neighbours put on the industry and government started to pay off. “We pushed them so bad about how little they knew that they made the chemical engineers go back and take a course,” he says. “If you didn’t pass the course you weren’t allowed to come back.”

Still, the lack of robust monitoring and regulation is a constant theme of concern among residents. Thomas’s years of working in oil industries around the world leaves him feeling nothing but frustration when he sees what’s happening around him and his neighbours.

“We do things right here in Alberta that 20 years ago when I was working in Venezuela would not have been allowed.”

A Constitution that reflects our values

According to Lars Haltbrekken, chair of the environmental non-profit Friends of the Earth Norway, his country’s constitutional recognition of environmental rights came as the result of a gradual societal evolution.

“The inclusion of environmental protection in our constitution did not mark a radical break with the old political order, but more of an affirmation of a long process.”

Canadian environmental lawyer and author David Boyd has spent the past several years writing about that process. Following in the footsteps of David Estrin and John Swaigen, he’s outlined how the rapid adoption of environmental rights around the world reflects a gradual change in how human beings value the environment. In his view, we’re ready.

“The same evolution in values has occurred in Canada. But the Canadian Constitution remains silent on the environment.”

If Canada recognized its citizens’ right to a healthy environment, Boyd argues, we would start to benefit in a variety of ways, including better health and environmental protections, a stronger democracy with a better-informed citizenry and — perhaps, most importantly — a level playing field between competing economic and social rights when it comes to decision-making.

Protecting the people and places we love

It’s the kind of balance Cochrane residents want. For Gary Tresidder, it would mean taking a long, hard look at whether industry is doing everything it can to get it right.

“It can be done. All we need is some willingness.”

It can be done. All we need is some willingness.

He walks outside through thick grass, inspecting his horses and pausing to watch a gawky, brand-new foal ducking under its mother for a drink of milk. He motions over to a nearby corral of larger horses meant for barrel racing. His daughters are only interested in riding those, Tresidder says with a laugh. The inside of his house is scattered with pictures of his two girls, now nearly grown, in uniform at various competitions and events.

“We probably have this debate every second day, whether to move or not. We just love this area. We’ve got our attachments here, we’ve got our memories here, we’ve got our history here, my kids grew up here. You know, we should move but it’s so hard.”

Tresidder and his neighbours face difficult decisions about their future. The life they’d envisioned for their families was rooted in the vision of Canada as a place where a healthy environment was supposed to be a given — an idea strongly felt as part of our national identity.

An overwhelming majority of Canadians support the right to a healthy environment and over 80 per cent agree our Charter should include it as a fundamental right, according to recent surveys.

More than 110 nations around the world — well over half — recognize their citizen’s right to live in a healthy environment. But not Canada.

After constitutional reform failed in the 1990s, Canada’s federal and provincial political leaders backed away from any attempt to reopen it. It seems the idea of another constitutional debate in this country is off limits to our leaders.

From his Geneva office, Svend Robinson is quick to challenge that assumption.

“I think we have to be very careful to distinguish between what Canadians would be willing to do and what political leaders want to do.”

Robinson has seen many enormous, encouraging changes since he first stood up in the House of Commons. “Back then, if you talked about global warming or climate change, people would have looked at you like you were deranged.” Today, he sees everyday Canadians standing up for the people and places they love. The community of Cochrane is a prime example of the growing movement.

“A campaign today to respect a clean and healthy environment — is that a good thing? Does it make us as a country stronger? Absolutely. Go for it.”

—

“Broken Ground” is a project of the David Suzuki Foundation. Learn more about our work on environmental rights in Canada.

Written by Alvin Singh and Alaya Boisvert, edited by Gail Mainster and Ian Hanington.

Special thanks to Greg Francis for video of David Estrin and John Swaigen, and Hans Asfeldt and Alison Bortolon, members of the Alberta Voices team who started the original research into the impacts in Cochrane.

Join the Blue Dot movement

Stand with people in Canada who are asking all levels of government to recognize our right to clean air and water, safe food and a stable climate.