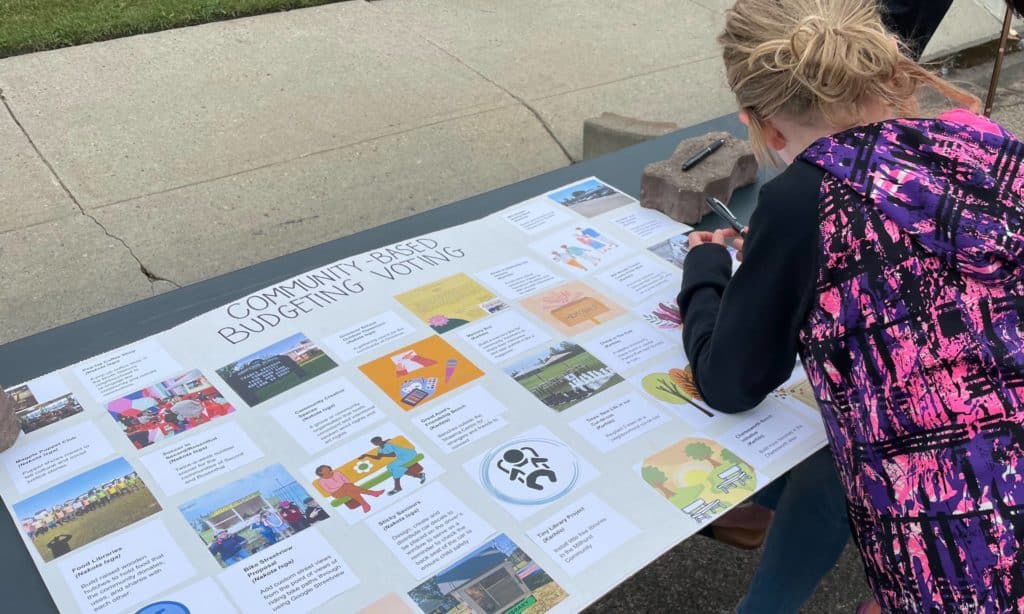

Edmonton residents learned about and voted for their favourite community-based budgeting projects. (Photo: Keren Tang)

Edmonton is located within Treaty 6 territory and within the Métis homelands and Métis Nation of Alberta Region 4. It is the traditional territory of many First Nations such as the Nehiyaw (Cree), Denesuliné (Dene), Nakota Sioux (Stoney), Anishinaabe (Saulteaux) and Niitsitapi (Blackfoot).

Can a local government transform a community by including residents in budget decisions? Advocates of a process called “participatory budgeting” think so. Indeed, this process has been shaping communities around the world — from Porto Alegre, Brazil, to Lisbon, Portugal, and most recently to Edmonton, Alberta.

What is participatory budgeting?

According to the Participatory Budgeting Project, it’s “a democratic process in which community members decide how to spend part of a public budget. It gives people real power over real money.”

Participatory budgeting invites residents of all ages and backgrounds, whether or not they’re old enough or formally registered to vote, to present ideas for projects that could improve their communities. Residents vote to determine which projects should receive funding and work with government officials to implement them.

As the Participatory Budgeting Project explains, uplifting residents’ ideas and perspectives “often makes up for gaps in official knowledge, leading to better, more equitable and innovative solutions while also bringing the people and their government closer together as a community.… Historically disenfranchised groups are able to participate, and historically marginalized ones tend to participate more, leading to the government hearing new voices.”

In 1989, Porto Alegre became the first city to implement participatory budgeting with the hope of reducing poverty. Not only did it succeed in that respect, it also helped reduce local child mortality by nearly 20 per cent. Since then, it’s been implemented in more than 7,000 cities worldwide, by different levels of government, schools, institutions and housing authorities.

Edmonton councillors get inspired

Decades after participatory budgeting took hold in South America and thousands of kilometres from its birthplace, two Edmonton city councillors — Keren Tang in Ward Karhiio and Andrew Knack in Ward Nakota Isga — implemented a project of their own. Their goal was to develop and test a process for participatory budgeting that worked for Edmonton and would “facilitate a conversation about community resilience, social connection and ecological transition.”

“Participatory budgeting has always been an interest of mine,” says Coun. Tang. “It was part of the platform I ran on during the 2021 municipal election with a goal of leveraging this process to stimulate hyper-local climate actions and fundamentally shift the way Edmontonians engage with local government.”

Coun. Knack was interested in involving people who don’t normally participate in politics. “When Coun. Tang said she was ready to do this, I knew this was the right time to try it, as we were able to join forces through our ward offices,” he says.

They’d both been inspired by how participatory budgeting had made municipalities worldwide, including many in Canada, more sustainable and resilient. For example, in 2020, the City of Montreal allocated $25 million to projects submitted and selected by the public. Winning projects included creation of mini-forests that improve access to urban nature, installation of fountains for reusable water bottles in poorly served locations and transformation of the upper storey of a parking garage into a public space for urban agriculture, arts and culture. More than 20,000 Montreal residents voted on the proposed projects.

In 2020, the City of Montreal allocated $25 million to projects submitted and selected by the public. Winning projects included creation of mini-forests that improve access to urban nature, installation of fountains for reusable water bottles in poorly served locations and transformation of the upper storey of a parking garage into a public space for urban agriculture, arts and culture.

The community-based budgeting project

Couns. Tang and Knack each allocated $25,000 from their ward budgets to the project — a relatively small and low-risk amount, but enough to support meaningful projects. They gathered a team that included staff from both ward offices and a project coordinator, as well as community partners: the civic technology group Beta City YEG and two BIPOC-led community organizations (Islamic Family and Social Services and Ribbon Rouge Foundation) that connected students seeking work experience to the project.

Based on public feedback, the team decided to call their project “community-based” rather than “participatory” budgeting.

Between April and July 2022, they held three free workshops where residents could brainstorm and refine ideas for projects that would improve health, resilience and connection in their communities. They also created an online community brainstorm board where those who couldn’t attend in person could share ideas and receive feedback.

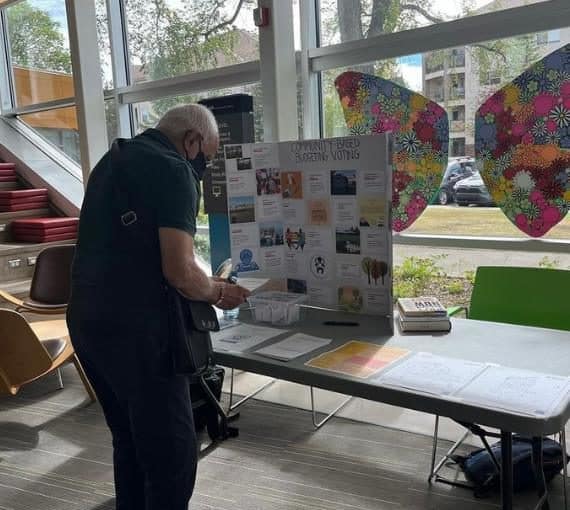

Twenty-three projects were submitted, and there was enough funding to support them all. But the team still wanted to engage the public in a voting process, so they invited residents to learn about and vote for their favourite projects. Voting was open to everyone, regardless of age or where in Edmonton they lived, and took place online and in person at three libraries and various community events.

Funded projects

The 23 community-based budgeting projects included:

- a free, publicly available collection of visuals of Edmonton’s bike paths, which allows residents to preview paths in preparation for their rides

- local food libraries

- a Pride walkway painted in a transit centre to make it more welcoming and inclusive

- trees planted in a suburban desert

- a chess installation and regular chess gatherings in a park

- welcome kits with essential items to give refugees arriving in Edmonton a sense of community

(Photo: Rajay Maggay)

Project successes

The project was successful in several ways, perhaps most importantly because it sparked collaboration and new relationships, both within and between the two wards. Through the workshops, residents made new connections as they identified shared interests and opportunities to learn together. Some participants went on to share supplies and expertise and help promote other project events.

The project also succeeded in engaging a diversity of community members.

Salimah Valiani, executive adviser for Ward Karhiio and part of the project team, recalls, “We were able to reach different people than we usually see. We saw a lot of people who aren’t connected to community leagues, and I thought that was great because all these people have amazing ideas and they just need a little push and a little grant funding to help bring them to life.… I think building those connections and empowering them will help them become champions in their neighbourhoods and continue to build relationships with the city and with our ward office.”

I think building those connections and empowering them will help them become champions in their neighbourhoods and continue to build relationships with the city and with our ward office.

Another project success, according to Coun. Tang, was the ability to “seed a lot of small projects with big impacts.”

The refugee welcome kits, created by a Girl Guides group, is an excellent example. “It’s just one kit,” Tang says, “but the Girl Guides raised a lot of in-kind donations from other groups. So, some groups leveraged [the funding] with donations for greater impact.”

Advice for other municipalities

Coun. Tang acknowledges that many municipalities in Canada don’t have ward budgets and therefore aren’t able to dedicate funds to such projects. But for officials or city staff that are interested, she and Valiani have some advice.

First, mentoring and relationship-building with community members takes time and effort. Staff from both ward offices spent many hours coaching and guiding the participants as they developed their ideas.

Second, the project team should think of the process as a chance to learn from the community.

“It was our first time doing community-based budgeting in Edmonton; we didn’t quite know what to expect from it,” Valiani says. “Our project team had to focus on the feedback we got from community members — what would support them, what kind of resources do they need, how much money works well for a small-scale project.… You have to stay nimble and agile, which is one of the hardest things to do, but I think it really helps with the process.”

Their third piece of advice: community-based budgeting inevitably involves giving up control.

Coun. Tang recalls hearing several participants declare, “We can’t believe how much you trusted us!”

“I think that trust is incredibly important,” she says. Participants told her that when they apply for a typical government grant, they get overwhelmed by demands for complicated applications and reports, even if it’s just for a few hundred dollars.

“It makes it really unfeasible for everyday people to participate,” she says. She and Coun. Knack kept project barriers low with simple submission and reporting requirements.

“I’m comfortable with this process, with giving up control, because in my experience that always leads to the best outcome,” says Tang, who has a background in community organizing.

“What stood out to me about this process was how easy it made it for a single citizen to make a change in their community. It really puts the power in the hands of the people, and the support from the ward has been incredible.” – community-based budgeting project lead

Advice for residents

And for residents who want to see community-based budgeting in their communities?

“We generally deal with complaints,” Coun. Tang says. “Very rarely do we get an idea. And when that happens, we’re like, this is fantastic! How can we support you to make [your idea] happen?

“The more residents can be idea-oriented and solutions-focused, the better response they’ll get from their elected official and the staff who support them.

“If you’re coming forward with an idea and are really open about it, there will be opportunities to build a relationship with your elected officials and see how they can help support you or even help you brainstorm ways to get your ideas off the ground.”