For much of human history we lived close to the natural world. As civilization evolved we became increasingly urbanized, and for most of us it can be a challenge to communicate why this loss is important. We know species diversity is critical to the healthy functioning of ecosystems that provide services on which humans depend. But could we live with fewer? Some would argue we could do without mosquitoes and other annoying critters. We could keep the ones we want and those that are useful to us. Do we need biodiversity to keep humans healthy?

According to an article in Conservation magazine, there is a link between biodiversity and human health. Ilkka Hanski and his colleagues at the University of Helsinki compared allergies of adolescents living in houses surrounded by biodiverse natural areas to those living in landscapes of lawns and concrete. They found people surrounded by a greater diversity of life were themselves covered with a wider range of different kinds of microbes than those in less diverse surroundings. They were also less likely to exhibit allergies.

What’s going on? Discussion of the relationship between biodiversity and human health is not new. Many have theorized that our disconnection from nature is leading to a myriad of ailments. Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods, says people who spend too little time outdoors experience a range of behavioural problems, which he calls “nature deficit disorder”. It fits with theories of modern ecology, which show systems lacking in biodiversity are less resilient, whether they’re forests or microbial communities in our stomachs or on our skin. Less resilient systems are more subject to invasion by pathogens or invasive species.

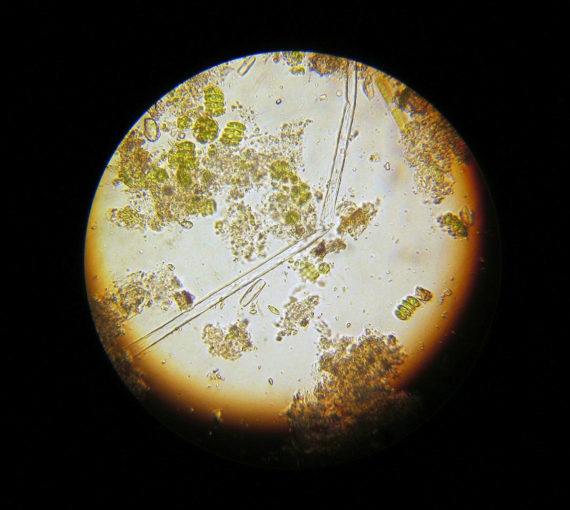

Hanski studied a region in Finland where few people move far. He randomly selected 118 adolescents in an equal number of homes. Some were in the city and others in woods or on farms. The team collected skin swabs from subjects and then measured the biodiversity of plants around each house. Their data revealed a clear pattern: higher native-plant diversity appeared to be associated with altered microbial composition on the participants’ skin, which led in turn to lower risk of allergies.

Hanski and his colleagues found that one group of microbes, gammaproteobacteria, appears to be associated both with plant diversity and allergies. And it didn’t matter whether they considered allergies to cats, dogs, horses, birch pollen or timothy grass. People with more diverse kinds of gammaproteobacteria on their bodies were less likely to have allergies.

The immune system’s primary role is to distinguish deadly species from beneficial and beneficial from simply innocent. To work effectively, our immune system needs to be “primed” by exposure to a diverse range of organisms at an early age. In this way it learns to distinguish between good, bad and harmless. If not exposed to a wide array of species, it may mistakenly see a harmless pollen grain as something dangerous and trigger an allergic reaction. We also know that bacteria and fungi compete. Fungi are often associated with allergies, and it could be that high diversity of bacteria keeps the fungi in check.

A conclusive explanation for Hanski’s observations is not yet available. More research is needed. But we know we evolved in a world full of diverse species and now inhabit one where human activity is altering and destroying an increasing number of plants, animals and habitats. We need to support conservation of natural areas and the diverse forms of life they contain, plant a variety of species in our yards, avoid antibacterial cleaning products and go outside in nature and get dirty — especially kids. Our lives and immune systems will be richer for it.now live in cities. As we’ve moved away from nature, we’ve seen a decline in other forms of life. Biodiversity is disappearing. The current rate of loss is perhaps as high as 10,000 times the natural rate. The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s 2008 Red List of Threatened Species shows 16,928 plant and animal species are threatened with extinction. This includes a quarter of all mammal species, a third of amphibian species and an eighth of bird species. And that’s only among those we know about; scientists say we may have identified just 10 to 15 per cent of existing species.