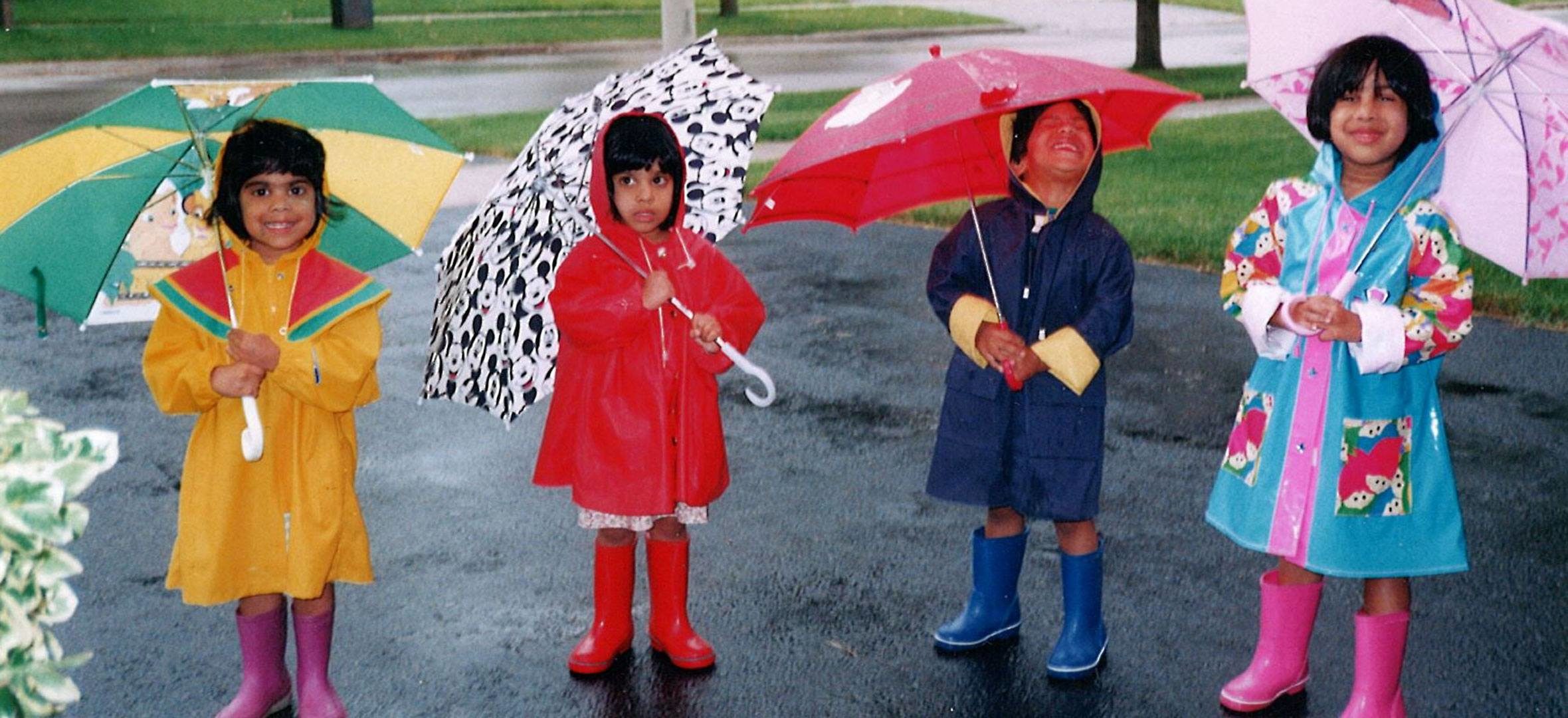

Maya Menezes is a daughter of immigrants from India and Pakistan. Maya grew up in Toronto, the territory of the Dish With One Spoon agreement. She specialized in food sovereignty, social justice equity and environmental studies at the University of Toronto. She’s director of development for the Toronto Environmental Alliance, works with migrant justice organization No One Is Illegal -Toronto and serves on the boards of Toronto350 and Web of Change.

“In a world of more than seven billion people, each of us is a drop in the bucket. But with enough drops, we can fill any bucket.” — David Suzuki

What inspired you to work on environmental issues?

Growing up in the concrete jungle of Toronto, I never understood nature’s importance or connection to the land. My family travelled extensively in our little minivan. I hugged ancient redwoods in Big Sur, sat on cliff sides in Halifax and hiked the Bruce Trail. But I didn’t “get it” until I moved to British Columbia. I discovered the wild and my place in it on Coast Salish territories.

Yet Vancouver Island misses things crucial for me: people of colour, diversity, a thousand languages spoken on every street corner. I realized that the country on our postcards is a privilege for those who can afford it, that travel is a class privilege that comes at great expense of those in need.

I wanted to work in international development, until I came to understand it as neo-colonialism. I couldn’t reconcile my want for adventure with that oppressive, marginalizing framework. So I moved back to Toronto to far less glamorous, but far more decolonizing work.

What keeps you committed to promoting environmental sustainability?

I’m inspired by the connections between worker disenfranchisement, institutionalized racism and climate disaster. I’m proud to ally with the End Immigration Detention Network and No One Is Illegal, who are challenging the constitutionality of indefinite detention in Ontario. The incarceration of black and brown bodies is directly tied to climate change, mass migration and the global refugee crisis. My TEA colleagues are fighting for Toronto to adopt a climate strategy that will dramatically reduce GHG emissions and work towards poverty reduction, energy retrofits and safe subsidized housing. This is climate justice in action. It gives me hope for the future. Toronto organizations are fighting for the same outcomes in different ways. Reaching out across imaginary borders to build lasting solidarity is the only path I see forward.

What did you learn from attending COP22 in Marrakech?

There, I saw a group of heavily tokenized Indigenous and brown folks tossed haphazardly into a white system that was more carefully staged photo ops and grandiose symbolic gestures than real action or change. The most mind-blowing thing wasn’t COP itself, but the marginalized folks. I saw the most beautiful resistance on the fringes. Hundreds of Indigenous peoples from across the world came together to share strategy and solidarity with Standing Rock. Fellow South Asians and femmes from around the world shared tactics, successes and failures, so that we can all learn how to build power. It reminded me that real change always happens on the ground, with communities on the front lines, and that honouring resistance and supporting it from behind are the foundational building blocks on the life-long road of being an ally.

How can the environmental movement be more accessible, relevant and inclusive to folks from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds?

Signing petitions against the tarsands without Indigenous solidarity, pipeline blockading and honouring the treaties is not resistance. Buying organic without understanding the plight of racialized migrant workers is not justice.

The environmental movement is Indigenous, black, brown, poor and has been happening for thousands of years. The best thing I can do is join front line communities in their struggle for dignity and rights. This means leading from behind and doing what is asked of me — amplifying voices, doing the behind-the-scenes grunt work of movement planning and fundraising, or using my privilege to help more marginalized folks navigate legal, housing and policy pathways.

What’s the “Brown Caucus” and why is it important?

The Brown Caucus is a group of folks who’ve worked in climate organizations and youth-mobilizing forces most of our lives. We were saddened by how difficult it is for youth in the South Asian diaspora to enter climate spaces. Some of it has to do with “model immigrant” socialization — the trauma of families leaving war and poverty, hoping for the best for their kids. The pressure to enter a high-paying corporate job is crippling. It usually distances youth from decolonization and justice work. We wanted to open a space where young, brown folks could come together and learn how to enter the environmental movement in a safe way, and vent about micro-aggressions and institutionalized racism — including racism we face in our daily jobs. We address what it means to be racialized settlers on these territories, the rampant anti-black racism in South Asian communities, and how to manage the road ahead.

What advice do you have for creating sustainability initiatives in urban communities?

Learn on whose back your community exists — whether that’s your food system, energy production or your place in urban gentrification. Work every day for their liberation. Your liberation is directly tied to theirs. Fearlessly fail forward.

Nikki Sanchez

Nikki Sanchez is a Pipil/Maya and Irish/Scottish academic, media maker and environmental educator. After two years as David Suzuki’s Queen of Green, she partnered with Telus STORYHIVE on the first ever mentorship funding for emerging Indigenous filmmakers. She also helped create RISE, an eight-part VICELAND documentary series on global Indigenous resurgence, which debuted at Sundance in February 2017 and received global critical acclaim, including Best Documentary at the Canadian Screen Awards.