Shady Hafez, centre, participates in a traditional Anishinabe powwow dance. (Photo: Moontee Sinquah)

Shady Hafez is an Algonquin Anishinabe Syrian member of Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg from Ottawa, Ontario. Shady is working to develop land-based healing work for people in his community. He’s also a traditional powwow dancer, an artist specializing in beadwork, quillwork and sewing, and a proud Dad. He has a bachelor’s degree in law and Canadian studies, and a master’s degree in Indigenous governance from the University of Victoria.

“In a world of more than seven billion people, each of us is a drop in the bucket.

But with enough drops, we can fill any bucket.” — David Suzuki

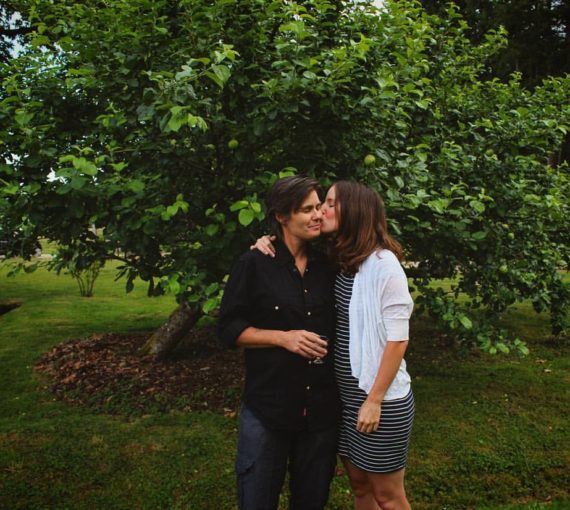

Shady Hafez (Photo: Peter Stockdale)

How does your connection to the land shape your identity?

When I return to my ancestral territories, I feel connected to my original way of life, teachings and histories. I participate in cultural activities such as dancing, singing and ceremonies, but land-based activities such as hunting, fishing and trapping feel different.

Growing up mostly in the city, I was fortunate to have family members connected to the land. My mother often sent me to my uncle to hunt, trap, fish. Those experiences helped shape me. Being on the land reinforces who I am, who my family is and what lands are traditional to my people. It helps me know where I belong in this world.

The lands we use for our traditional practices are those the Creator bestowed on us. They will always be in our people’s care. Without that connection, I’m not sure where I’d be today.

Why did you return to your community after university to do cultural land-based healing work?

After finishing my master’s degree, I returned to my community to give back for all the support that the community has given me. I wanted to use my academic and professional abilities and my knowledge of culture, ceremony and land-based practice in a way that would benefit the community.

I intended to work on police and justice reform, things I’m passionate about. But I was offered a position as co-ordinator for my community’s mental wellness team and began to see a real need for more substantial mental health services.

I examined how we’re currently utilizing our culture to develop positive identity and mental wellness, and saw that we’re disconnecting it from its root, the land. I spoke with community knowledge holders, professionals, elders and youth and began to understand that the community wanted something more. I started researching how to develop a program that helps people with mental health issues utilizing the land as the source and site of healing.

Being on the land reinforces who I am, who my family is and what lands are traditional to my people. It helps me know where I belong in this world.

What’s the connection between mental health, culture and environment?

The ongoing effects of colonialism is one reason why people in our communities are suffering from a wide array of mental health issues. Colonialism continues to decimate Indigenous Peoples’ identities via many tactics, including assimilation, education, the economy, land dispossession, violence and land degradation.

One of the biggest assaults on our identity is the assault on our lands. We’ve been removed from our lands. They’ve been decimated by the resource extraction industry. The land and our use of it formed our identity for thousands of years. When we’re removed from our lands, we’re removed from understanding how we exist as a distinct people. We lose our ancestors’ teachings, and the teachings of the land itself and how all creation exists with one another.

By not knowing who we are, we forget how to deal with life’s many issues. We no longer know how to address conflicts between individuals and families, addictions, sexual violence and other issues in ways that reflect our Anishinabe worldview. We often resort to colonial ways of healing or dealing with these issues, but colonial mechanisms do not work for our people.

We must reignite our original way of being, a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world. We must revitalize our identities. To do that we must return to the land and to our ancestors’ practices that informed their identities, ways of being and ways of knowing the world. The problem is that with the current state of environmental degradation, our ability to follow in our ancestors’ footsteps is becoming harder.

What’s changed in your territories since you spent time on them growing up?

The biggest impacts are the affects of forestry. Clear cutting is decimating land in areas we use for hunting, fishing, trapping and other land-based activities. There’s a significant decrease in sightings of moose and deer, in fish numbers and types of fish.

When we’re removed from our lands, we’re removed from understanding how we exist as a distinct people. We lose our ancestors’ teachings, and the teachings of the land itself and how all creation exists with one another.

How does land, language and story form a worldview that instructs Indigenous People how to engage with flora and fauna in a reciprocal, sustainable way?

I’m not a knowledge holder so I can’t answer this question from a position of authority. But, my understanding is that everything in our natural environment is connected in one way or another. And when we do something to one thing, all aspects of creation are affected.

We must always be cautious about what we’re doing on the land. It might seem that our actions won’t have an impact, that they’re disconnected. But they are connected and everything has an effect. We must visually see how the natural environment interacts with itself, how plants, trees and animals react to changing seasons, environmental disasters, death and life. When we see how creation reacts to these things, we see how we need to react to these things. We can learn from the different lessons that the environment teaches us.

What advice do you have for non-Indigenous Canadians who want to be allies?

Work your hardest to return lands to Indigenous Peoples. Ensure that when those lands are returned we’re still able to use them the way we see fit. You don’t have to up and leave, although in some instances that may be required. Lands Canada isn’t utilizing should be returned to Indigenous Peoples without question.

Work to ensure that our environment is sustainable for our people as well as our next seven generations, because if we don’t have access to our lands in the same way that our ancestors did, it’s going to be difficult for us to revitalize our ways of being, which are tied to all aspects of our physical and mental wellness.

Nikki Sanchez

Nikki Sanchez is a Pipil/Maya and Irish/Scottish academic, media maker and environmental educator. After two years as David Suzuki’s Queen of Green, she partnered with Telus STORYHIVE on the first ever mentorship funding for emerging Indigenous filmmakers. She also helped create RISE, an eight-part VICELAND documentary series on global Indigenous resurgence, which debuted at Sundance in February 2017 and received global critical acclaim, including Best Documentary at the Canadian Screen Awards.