In May 2019, the Blueberry River First Nations court case against the province began: the case focuses on the fact that the cumulative impact of industrial activities has significantly impacted the lands and wildlife within Blueberry’s traditional territory and, accordingly, their treaty rights.

They further noted that their territory, which lies over the Montney Basin, has become a “hub” or “epicentre” of oil and gas activity and has been “demonstrably and disproportionately impacted, even within the region.” Oil and gas development includes pipelines, seismic lines, wells pads, oil and gas facilities, roads and other developments and authorizations, such as water withdrawals. There is also extensive forestry in the territory.

“Ultimately, the cumulative effect is a transformation of the landscape that does not permit the Plaintiffs to purse their traditional activities in a way that has the cultural or economic significance that was integral to their mode of life,” Blueberry River First Nations argued.

Blueberry River wants the province to recognize the cumulative impacts and infringement and “to amend the basis on which it acts in the future, such that it proceeds on a ‘different footing’ that is consistent with and accommodates BRFN’s Treaty rights.”

Meanwhile, while the case is heard, the level of cumulative disturbance in Blueberry’s traditional territory continues to rise.

The question of ‘modernity’

During the opening of the trial of Blueberry First Nations against the province of B.C., the province responded to Blueberry River’s claims (see overview above) by suggesting that the First Nation needed to “modernize” its livelihood. As their legal representative stated, “Reserve lands may provide for the ‘livelihood’ of First Nations in modern times through agriculture, ranching or the exploitation of the subsurface rights.”

This premise — that the case could handily be solved by assimilation — is racist. But it is also a misinterpretation of the treaty’s promise and of the aspirations of Blueberry First Nations community members, as heard in the opening arguments.

The lawyer representing Blueberry, Maegen Giltrow, was clear that the nation wasn’t merely holding onto the past and that many members participated in the “modern” economy. Commitments were made during treaty negotiations, she outlined, that ensured that while the traditional way of life could exist within a mixed economy, the traditional mode of life would nevertheless “be essential and endure.” What the community is arguing for is enough space to choose either or both traditional and current ways of life — the freedom of choice.

As presented during opening remarks, between 2013 and 2016, the “modern” economy had resulted in approvals in Blueberry’s territory of more than:

- 2,600 oil and gas wells,

- 1,884 kilometres of petroleum access and permanent roads,

- 740 kilometres of petroleum development roads,

- 1,500 kilometres of new pipelines,

- 9,400 kilometres of seismic lines, and

- harvesting of approximately 290 forestry cutblocks.

Further, as of May 2018, 10,672 non-operating oil and gas well sites in B.C. had not been restored, a significant portion of which would be concentrated in the plaintiffs’ territory.

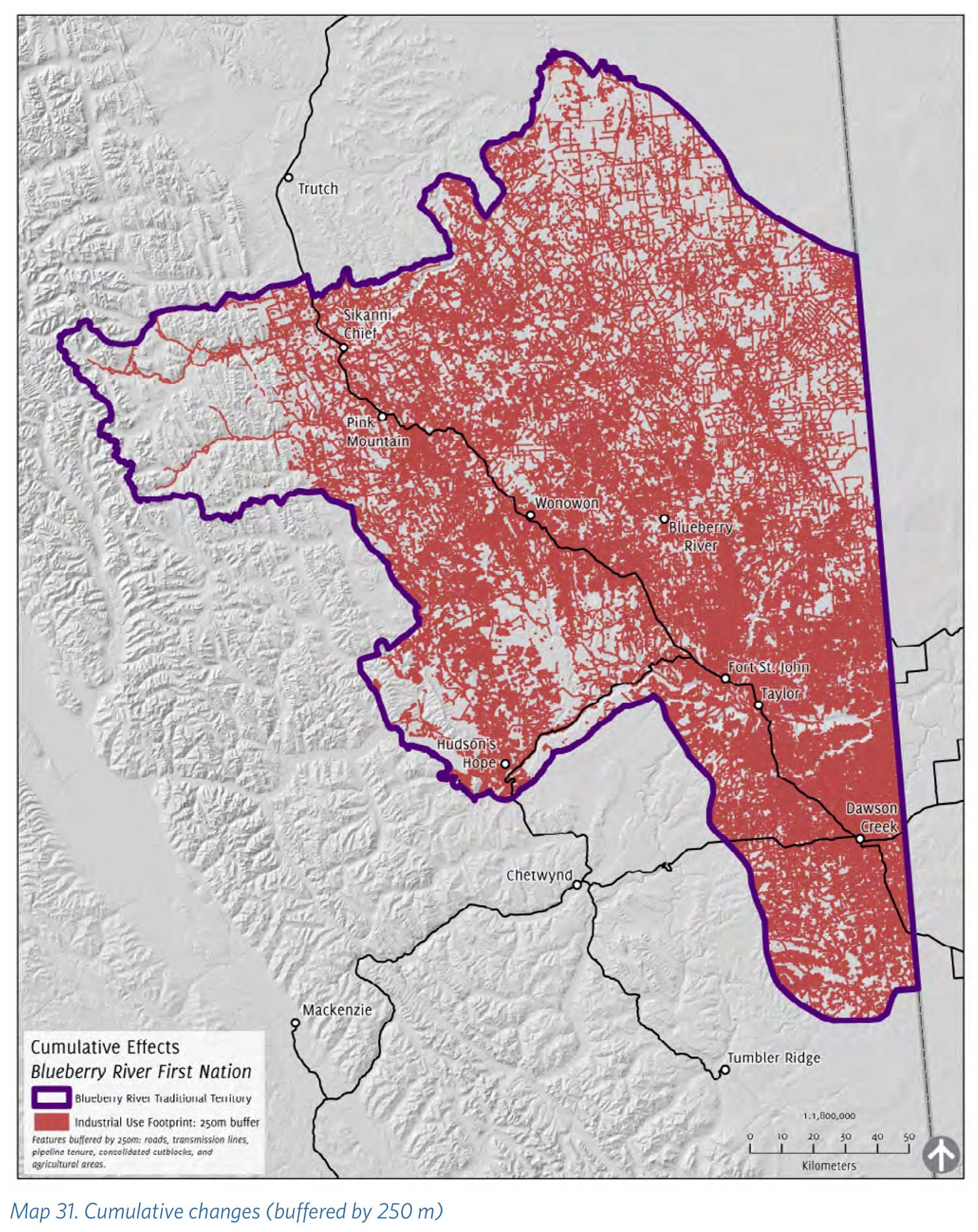

Below is an image of the level of cumulative disturbance in Blueberry’s traditional territory from a report DSF did with the community and Ecotrust in 2016. It doesn’t include disturbances since 2016, nor pending threats such as flooding that would result from the proposed Site C dam.

When speaking about the remedy sought by the community, Blueberry’s lawyer outlined a vision not of travelling backward in time but of travelling forward, to a more ecologically responsible relationship with the land. She noted that:

There are numerous opportunities to extract resources at reasonable rates in the region while reducing impacts on the Plaintiffs’ territory and rights, which have either not been taken at all, or which have only recently been considered, including, for example: ensuring the harvest of timber is not disproportionally focused on the core of Blueberry’s territory; ensuring sufficient recovery time in areas that have been clear-cut before harvesting further on adjacent blocks; reducing waste wood from forestry and oil and gas that is cut but then left or burned; compelling greater use of horizontal drilling and existing sites in oil and gas development to reduce surface disturbance; ensuring any new development is mitigated by immediate restoration of a greater portion of land in order to begin to close the gap between development and restoration in the territory; implementation of protected areas at least in proportion to those found elsewhere in British Columbia.

The opening arguments gave me pause regarding interpretation of the “modern” world. “Modern” is defined as something relating to the present or recent times as opposed to the remote past.

Is this really where we are at — that ever-expanding exploitative resource extraction activities continue to define our moment in time as a society? That even when science tells us that cumulative impacts are imperiling wildlife survival, provinces continue to push for the status quo?

I believe the province’s approach is outdated, that its clutch on the old-school model of grow-at-all-cost resource extraction is blind to the current moment of social evolution. The new model of power is AOC, not the Koch brothers. We are finally celebrating diversity instead of advancing assimilation — even recognizing that diversity makes us more economically competitive. As a country, we’ve already turned the corner to a less exploitative future. Canada’s clean energy sector is growing faster than the rest of our economy. There are already 50 per cent more jobs in clean energy (including renewable energy production and distribution, energy efficiency and sustainable transportation) than in oil and gas and mining combined. A recent study of the potential of restoration in B.C. found, “Employment benefit estimates of caribou habitat restoration, when compared to current forestry sector employment for BC, suggest that the potential benefits of restoration might outweigh the opportunity costs to these traditional resource industries over at least a 20-year restoration period.” Movements around the world are growing to rewild areas, rather than continuing to pave them over.

In her concluding remarks, Giltrow stated, “the future is more important that the past.” Let’s hope the court system is also looking ahead (not back over its shoulder, like the province), and that its ruling falls on the right side of modernity.

This is the first article in a five part series on the legal challenge by Blueberry River First Nations against the Province of B.C. over treaty rights infringement.

Our work

Always grounded in sound evidence, the David Suzuki Foundation empowers people to take action in their communities on the environmental challenges we collectively face.