A totem in Campbell River, B.C. The David Suzuki Foundation's Coastal Tour visited a dozen communities in the traditional territories of 12 First Nations along Canada's vast Pacific coast where people spoke passionately about the connection between a healthy environment and economic, cultural and social rights.

Many Canadians see our country as a human rights leader, but a United Nations committee says we should do better. In early March, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights concluded that Canada’s lack of environmental protection and climate action mars our rights record.

The committee’s periodic review of Canada put our country’s commitment to providing basic necessities under the spotlight. Although the review’s authors commended Canada for several progressive steps, including the recently announced national inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, they expressed concern about the systematic lack of action on homelessness, poverty, access to food and other important obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Their recommendations on environmental protection and climate change policy were especially noteworthy. Although it’s evident that a healthy environment is the foundation of human rights to food, water, health and livelihood, the committee’s decision to push Canada to pursue renewable energy, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and establish stronger environmental regulations illustrates the growing global recognition of the link between environmental and human rights.

This recognition may be just emerging in international human rights law, but it’s nothing new to Indigenous people and many others who directly depend on nature for food and livelihood.

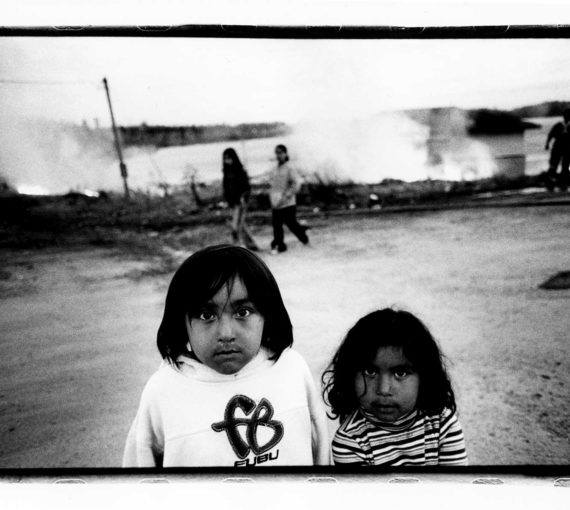

I heard this over and over again this past summer as I travelled with a team along Canada’s vast Pacific coast, visiting a dozen communities in the traditional territories of 12 First Nations. These people reside along 26,000 kilometres of British Columbia’s winding shoreline — home to trillions of plankton, billions of fish, millions of seabirds and thousands of whales, which live among forests of kelp and eelgrass, along underwater canyons and glass sponge reefs.

During the tour, we were welcomed with feasts that embodied the intersection of nature, food and culture, and we conducted more than 1,500 profoundly moving interviews with coastal residents. They expressed fears about threats to their way of life, including industrial projects that will catastrophically affect the environment and their livelihoods being approved with little or no consultation. They spoke passionately about the connection between a healthy environment and economic, cultural and social rights — because they live it every day.

One Pacific coast resident said, “When the fish come home or pass by Campbell River this whole community comes alive. Without the fish, a large piece of our island culture goes with them.” Another observed, “When we think of human rights, we think of equality, freedom, democracy. But what good are any of those if we don’t have clean air, soil and water? It has to start with nature.”

These and many other statements from Pacific coastal residents, which formed the basis of a David Suzuki Foundation submission to the UN committee, resonated at the international level. Observations of the effects of climate change on their communities — including unpredictable and extreme weather, decreasing snow and ice, water shortages, wildfires and salmon spawning failures — mirror the findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

This is a critical moment for Canadians as we face mounting pressure from climate change, ocean acidification and industrial development. With the longest coastline of any nation, our country holds a globally significant responsibility to protect its oceans, which are under threat from failures to address carbon emissions and ensure marine protection and management. Canada can start by acting on its commitment to protect 10 per cent of its marine environment by 2020, and by putting strict targets on greenhouse gas emissions.

We could also go a long way toward meeting our international human rights obligations by joining more than 110 nations in constitutionally recognizing the right to a healthy environment. Taking immediate steps to restore and enhance robust environmental protection, fully respect Indigenous rights to title and consultation, and protect ocean ecosystems from degradation and climate change is essential.

The growing international recognition of the disproportionate impacts on Indigenous and vulnerable people enhances the understanding that protecting the environment is as much about social justice as keeping ecosystems healthy.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Canada has the opportunity to mark the milestone by legally protecting all Canadians’ environmental rights and by recognizing that healthy oceans are a necessary condition for human health and dignity.