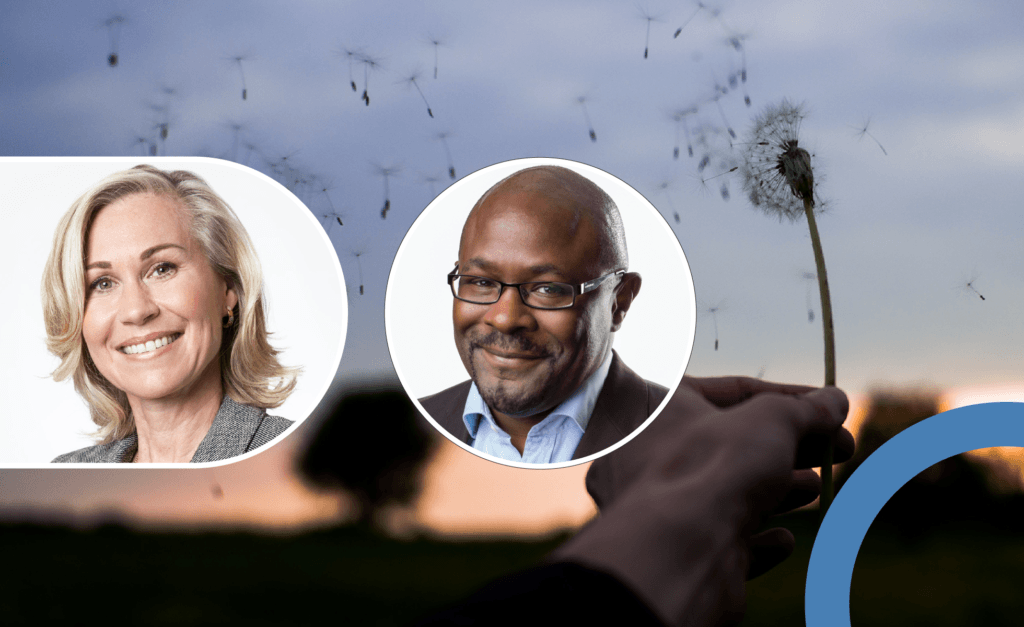

Former Toronto chief city planner Jennifer Keesmaat and Wellesley Institute CEO Kwame McKenzie.

“I can’t breathe.” Those were some of George Floyd’s last words — words that became the rallying cry at anti-racism protests around the world.

And now, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, have we ever been more aware, mindful or fearful of the air we inhale? Safe, clean air is something many of us have long taken for granted. Now we wear masks, and stay two metres apart, for fear of the invisible pathogens travelling through the air that could sicken us and upend our lives. With new immediacy, we’re suddenly aware that everything — right down to the air we breathe — is shared by all life on Earth.

Scientifically, there is no line between us and air. It is in us and flowing through our bodies. We are air. Whatever we do to the air — from burning fossil fuels to spraying pesticides to evaporating solvents — we do directly to ourselves.

In the second episode of my new podcast’s first season, “COVID-19 and the Basic Elements of Life,” I ask what this new awareness of air means for our shared future. I talk to Kwame McKenzie and Jennifer Keesmaat — two leading urban thinkers — about the future of sustainable living in our cities, and how achieving equity can help us all breathe a little easier. I also speak with David Suzuki Foundation climate policy analyst Gideon Forman about the future of sustainable urban living, and how cities can play a leadership role in building back better from COVID-19.

Kwame McKenzie is CEO of the Wellesley Institute. As a psychiatrist, academic and University of Toronto professor, he’s known internationally as a leader in the mental health field. He’s put a spotlight on the fact that not everyone has the same access to health care and how inequality is shaped by “social determinants of health”: race, income, education, access to food, location and community.

“Thinking about equity when thinking about sustainability and community development is something I think needs more attention,” he says. “The impacts of global warming in Canada are going to be vested significantly on poorer people and racialized people. The question is, ‘What do we do about it in an equitable way?’ Not just ‘What do we do about it?’ Most public health interventions increase inequities.”

This is our opportunity to go, ‘Hold on a minute here. We have a public health crisis. We have an environmental crisis. We have a social equity crisis. How can we drive forward just and sustainable approaches to community design?’

Jennifer Keesmaat

Jennifer Keesmaat is also actively involved in building that “new normal” in Canada. She’s an urban planner with an impressive resumé. Many might know Jennifer from her work as Toronto’s chief city planner and her run for mayor of Toronto in 2018. She was also named one of the most influential people in Canada by Maclean’s. Jennifer is among a number of Canadian leaders who say we need to remember the ongoing climate crisis as we rebuild from COVID.

“This is an opportunity for us to up our game,” she says. “This is our opportunity to go, ‘Hold on a minute here. We have a public health crisis. We have an environmental crisis. We have a social equity crisis. How can we drive forward just and sustainable approaches to community design?’”

Gideon Forman, climate change and transportation policy analyst with the David Suzuki Foundation, agrees. An active campaigner for sustainable transit and transportation issues in Toronto, his work touches everything from air pollution and emissions reduction to bike lanes and the linkages between friendship and a sustainable future.

“We know that millions of people around the world die each year because of air pollution,” he says. “In fact, they call it a pandemic. Over eight million people a year die globally from bad air. That’s more than the number that die from tobacco. So it really is a life-and-death issue protecting air quality.”

During the COVID-19 crisis, emissions have dropped slightly and some polluted skies have cleared, while governments are embracing reforestation campaigns for the social, mental health and environmental benefits. But how do we sustain it once the pandemic has passed? Surely, we can’t go on using the air as a dump for our wastes.

If there’s one place we’re especially mindful of the air we breathe, it’s the city, so let’s seize this once-in-a-generation opportunity to make our cities healthier, friendlier, greener, equitable and prosperous places to live.