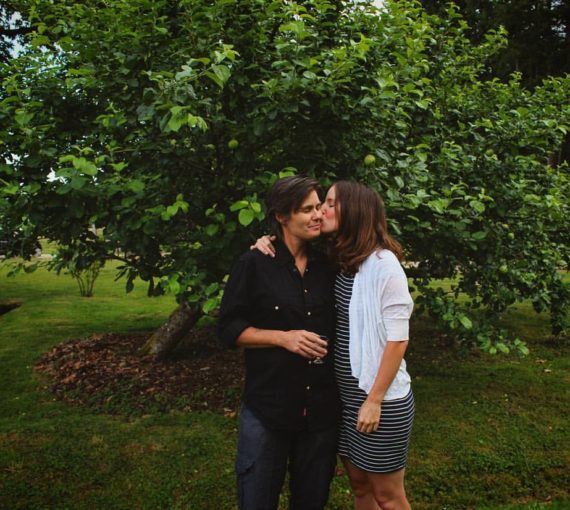

Candyce and Marius Paul of English River First Nation.

Marius and Candyce Paul are members of English River First Nation, a Dene band in northern Saskatchewan. Until 2013, they operated Reclaiming Our Youth Home Front School, addressing intergenerational impacts of residential schools and connecting students to their Treaty Ten territory home. Today they’re raising awareness about the risks and damages done by the uranium/nuclear industry.

“In a world of more than seven billion people, each of us is a drop in the bucket.

But with enough drops, we can fill any bucket.” — David Suzuki

How did you come to your current work?

When the first uranium mines opened on his grandfather’s trapline, elders tasked Marius with keeping watch on these companies that make “big bullets” (nuclear bombs). Youth tasked Candyce to protect their futures from nuclear waste burial. Along with other concerned people, they formed the Committee for Future Generations, to raise awareness throughout Saskatchewan and network globally.

What are the most significant issues?

Dene traditional knowledge is that the “black rock,” should stay underground — on pain of unleashing “demons” — and kept in its place by “Thunder Beings,” its continuously burning “sacred fire” acknowledged as a deity and never touched.

Promises of close monitoring pushed those ancient concerns aside. A case study done on the Environmental Quality Committee showed government and industry failed to take concerns seriously and omitted critical information.

After the uranium mines opened, the incidence of previously uncommon cancers and other rare diseases started to rise. Most people who worked in the mines suffered and died young of cancers. Physicians noting increases in diseases like lupus began asking for a baseline health study. That’s never been done. Cancer rates are at least one in seven people.

Studies on moose, caribou, fish and berries show these dangerous substances in foods people depend on. In communities around Lake Athabasca, where tailings from mines that fuelled Cold War nuclear weapons continue blowing and flowing into the lake, there are “limit fish intake” warnings on the docks. This may help limit the impact of heavy metals but doesn’t stop damage from ingested radionuclides. The World Health Organization admitted that even low doses of radiation exposure can lead to increase cancer risk.

Industry sets its own “as low as reasonably achievable” limits. Since the Fukushima meltdowns, many countries raised acceptable safety limits to accommodate additional global exposures.

When a physician asked for a baseline study at the October, 2012 Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission hearings for the relicensing of Rabbit Lake and McArthur River mines and the Key Lake uranium mill, the CNSC consulted Dr. James Irvine, northern medical health officer. He asked for a wellness study. It was funded with uranium mining companies Cameco and AREVA.

The Northern Health authority’s close relationship with the uranium mining companies — the Community Vitality Monitoring Partnership — is decades-long. Cameco funds a lot of community health care. It makes them look like good corporate citizens while masking the effects of the non-stop radionuclides and heavy metals they release into the environment.

With the advent of the global community, certain attributes were lost forever, and lands and waters desecrated. Contaminants and stress, destruction of world views, and a loss of the cultural and evaluative criteria eroded a once sovereign people.

What is “industrial colonialism”?

In the 1970s, the Saskatchewan government and uranium industry’s plan to open and operate new uranium mines promised economic prosperity. The fur trade and commercial fresh water fishery were being forced out. Unemployment was high. The chronic underfunding that keeps mainly Indigenous communities poor and in crisis eased acceptance of a controversial industry that opposed eons-old values.

They promised prosperity to Indigenous Peoples already poor, traumatized and disempowered by the reserve system and residential schools. They introduced a class system of “have and have not” based on consumer debt. The drug trade followed the money. Family structure still reeling from generations of kids raised in residential schools was further eroded by parents flying out to work at the mines.

With the advent of the global community, certain attributes were lost forever, and lands and waters desecrated. Contaminants and stress, destruction of world views, and a loss of the cultural and evaluative criteria eroded a once sovereign people.

Northern communities have not seen economic prosperity. Encouraged business opportunities were all tied to servicing the mines. Most communities have only a couple of stores. Some still have no roads.

More and more companies are being granted exploration permits, encroaching into Dene traditional hunting and gathering territories. Consultation is a farce. Company-hired consultants assess how little they can offer to disturb lands, waters, animals, plants and medicines. Company executives patronizingly view northern cultures as archaic.

What are your core messages?

We hope people who learn about this industry’s global impact and understand its risk into eternity will join us in saying “Kuh T’ah” —enough! The nuclear industry is not worth the damage it’s doing to the planet. They’ve failed at playing God by de-creating atoms, and humankind is ill-prepared to deal with the consequences.

The Nuclear Waste Management Organization was looking for a “willing host community” to accept a deep geological repository, targeting three northern Saskatchewan communities. The industry believed they would have a solution to deal with the nuclear waste after 70 years of tinkering and fragmenting atoms. But they’re no closer now than they were then.

We exposed information gaps and their reluctance to share the truth about the real risks of this untried experiment. Scientists are not all in agreement it’ll work. They won’t be able to stop the radioactivity from contaminating aquifers. We were successful in keeping them out of Saskatchewan but they’re still looking at five Ontario communities.

These companies need to be held accountable. They’ve affected the health of every living thing on the planet. They’ve contributed to global stress through nuclear weapons and power plant catastrophes. They’ve committed crimes against the yet unborn by damaging DNA.

We encourage our people to use their voices, to be who they have always been — the stewards of these lands.

How is your work supported?

In 2011, our forum explained nuclear waste dump plans. We started a petition and got resolutions from diverse organizations to ban nuclear waste storage in Saskatchewan. We ran a three-year educational campaign in the North and along transportation routes. We organized the 900-kilometre 7000 Generations Walk Against Nuclear Waste from Pinehouse in the north to the Regina legislature, doing town halls and interviews along the way.

In 2013, some of our youth took part in the Journey for Earth Walk from northern Saskatchewan to Ottawa, sharing knowledge and concerns on the impacts of uranium mining and the entire nuclear fuel chain. The day NWMO announced it was eliminating Saskatchewan from its search, the entire North breathed a sigh of relief.

Our expansive network now includes Europe, Australia, Greenland and the U.S. We help interpret industry jargon and raise awareness through info camps, academic forums, teach-ins, panels on nuclear industry impacts, and workshops at national and international events like the World Uranium Symposium.

We collect reports from whistleblowers concerned with a wide range of mine issues. We monitor radiation levels throughout the region. We help people access funds for culturally significant mapping, to prove the great value of these lands to the Dene, Cree and Métis. We bring in experts. Our FaceBook pages include links to scientific studies.

We encourage our people to use their voices, to be who they have always been — the stewards of these lands.

How can people support your work?

The business motto, “time is money” has rushed the world into a lot of detrimental decisions. We want everyone to slow down, discuss the big picture, and come to consensus about what we do from here on for the sake of the next 7,000 generations who’ll still be dealing with the nuclear industry mess.

We encourage people to fund our work or purchase original art, carved moose bone jewellery and beaded items connected to this land.

We need experts — biologists, geologists, hydrogeologists, health professionals, independent laboratories — to do studies to hold industry accountable. We need funding to calibrate the Geiger counters we use so we can be credible. We need motivated media to help us investigate and broadcast our stories.

Nikki Sanchez

Nikki Sanchez is a Pipil/Maya and Irish/Scottish academic, media maker and environmental educator. After two years as David Suzuki’s Queen of Green, she partnered with Telus STORYHIVE on the first ever mentorship funding for emerging Indigenous filmmakers. She also helped create RISE, an eight-part VICELAND documentary series on global Indigenous resurgence, which debuted at Sundance in February 2017 and received global critical acclaim, including Best Documentary at the Canadian Screen Awards.