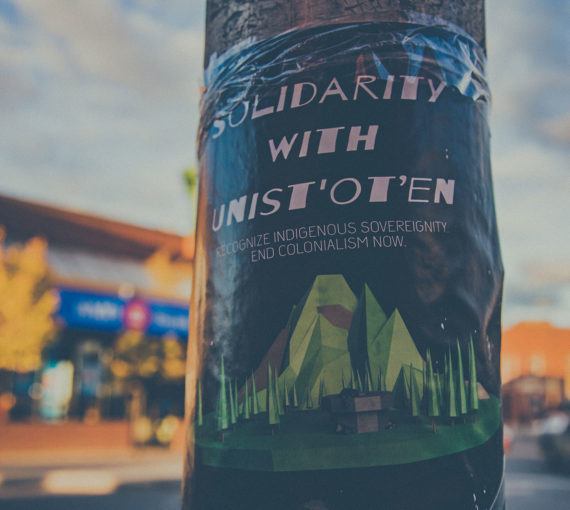

Governments must work with Indigenous Peoples to resolve issues around rights and title where treaties haven’t been signed and honour the treaties that have been. (Photo: Jason Hargrove via Flickr)

Actions by and in support of the Wet’suwet’en land defenders are as much about government failure to resolve issues around Indigenous rights and title as they are about pipelines and gas.

Some Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and their people are defending their rights to traditional practices, clean air and water and a healthy environment. They say the Coastal GasLink pipeline threatens those rights. The $6-billion pipeline, to ship fracked gas 670 kilometres from Dawson Creek to Kitimat for liquefying and export, is part of a heavily subsidized, $40-billion LNG Canada project owned by Royal Dutch Shell, Mitsubishi Corporation, and state-owned Petronas (Malaysia), PetroChina and Korea Gas Corporation.

The hereditary chiefs suggested an alternative route, but the pipeline company nixed it as too costly. The company and government point to support from elected chiefs and councils along the pipeline route, many of which have signed benefit-sharing agreements as a way to gain much-needed money for their communities.

But, as Judith Sayers (Kekinusuqs), University of Victoria adjunct professor from the Hupačasath First Nation, writes in the Tyee, “Neither the elected chief and band councils that support the pipeline, nor the federal or provincial governments, nor Coastal GasLink ever obtained the consent of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and their supporters.”

That’s partly because governments have failed to resolve issues around Indigenous rights and title, unless forced to after lengthy court battles, as with the 1997 Delgamuukw decision and the 2014 Tsilhqot’in decision, which recognized Indigenous title over unceded territories.

Perhaps governments are afraid that Indigenous rights and title would infringe on massive resource development schemes.

Perhaps governments are afraid that Indigenous rights and title would infringe on massive resource development schemes, although, under the previous decisions, they can still approve such projects as long as they can justify them and engage meaningfully with Indigenous titleholders.

If the principles set out in the Truth and Reconciliation report, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and court decisions are to have meaning, both levels of government must resolve issues around Indigenous rights and title and respect for Indigenous law.

One complication is that few people truly understand Indigenous governance systems. As Sayers writes, “The Wet’suwet’en were never defeated in a war, never surrendered their lands and never entered into a treaty.” Hereditary chiefs have jurisdiction over traditional territories, whereas elected chiefs and councils have authority on reserves. Elected band councils are an outcome of the 1876 Indian Act (and its precursors), enacted in part to destroy traditional governance systems and laws.

Some see the hereditary systems through a colonial lens — as monarchy or divine right — but they’re much more representative and consensus-based than many realize.

Colonial society has been inconveniencing and disrupting Indigenous lives for hundreds of years.

Now that actions have spread across the country, blocking rail lines, bridges, roads and ports, complaints about inconvenience and disruption are rife. But colonial society has been inconveniencing and disrupting Indigenous lives for hundreds of years. Now the RCMP, acting on behalf of extractive industries and government, are forcing Wet’suwet’en off their own territory.

Politicians rant about “protesters holding the economy hostage.” But Canada has held Indigenous people hostage up until the last residential school closed in 1996 — and longer through an unfair foster care system.

Recent actions are also calling attention to rapidly expanding fossil fuel development during a climate crisis, and the problems that come with giant resource projects, including violence against women. The Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls found direct links between extractive industries, “man camps” and increased violence against Indigenous women.

They also put a spotlight on society’s failure to respect the knowledge, laws and traditions of the people who have been here since time immemorial.

All Canadians should learn about Indigenous history and culture. We need to move beyond our narrow, extractivist, endless-growth mindset. The colonial worldview is failing us. We’re in a climate crisis, yet governments and industry are hell-bent on tearing up the landscape with fracking, immense oilsands mines, seismic lines, access roads and forestry to reap quick profits by selling it all to other countries. We need to realize that we have more to learn from Indigenous Peoples than they from us.

Governments must work with Indigenous Peoples to resolve issues around rights and title where treaties haven’t been signed and honour the treaties that have been. Until then, major resource projects that potentially infringe on these should be put on hold.