Growing recognition of the devastating harms our colonial past and still-existing systemic racism and oppression have perpetrated on Indigenous people has been met with increasing calls to redefine how we see our country, to give land back and to advance systems of economic reparation. (Photo: Tamara Herman via Flickr)

Canada as a nation was founded by “hewers of wood and drawers of water,” as late Canadian economist Harold Innis wrote in his 1930 book, The Fur Trade in Canada — using a biblical phrase to describe the country’s long-standing reliance on resource exploitation.

When the Hudson’s Bay Company started buying and exporting fur pelts, it created such a demand in Europe that the most commonly trapped creature, the beaver, was almost wiped out. Once settlers got settled, resource extraction expanded to logging and later oil and gas extraction.

Both have shown the same lack of appreciation for moderation as the fur trade. For example, less than three per cent of original old-growth forests that once graced British Columbia still stand, and the fossil fuel industry’s greenhouse gas emissions make an outsized contribution to climate change.

Indigenous Peoples were integral to the fur trade, but settlers eventually saw their presence on the land, and their sense of responsibility to it, as impediments to their ability to exploit and profit from its “resources.” And so colonial-settler governments moved Indigenous Peoples to reservations, while the newcomers reaped the benefits of their “property” — a concept unfamiliar to people who believe in shared responsibility to and reciprocity with land rather than “ownership.”

“Hard work is not what made Canadians richer than First Nations. … The difference was that their labour was paid off in free land stolen from Indigenous peoples. First Nations were left stranded on a vast archipelago of reserves and settlements, denied access to their wealth in territory.”

According to the 2021 Yellowhead Institute report “Cash Back,” “Hard work is not what made Canadians richer than First Nations. … The difference was that their labour was paid off in free land stolen from Indigenous peoples. First Nations were left stranded on a vast archipelago of reserves and settlements, denied access to their wealth in territory.”

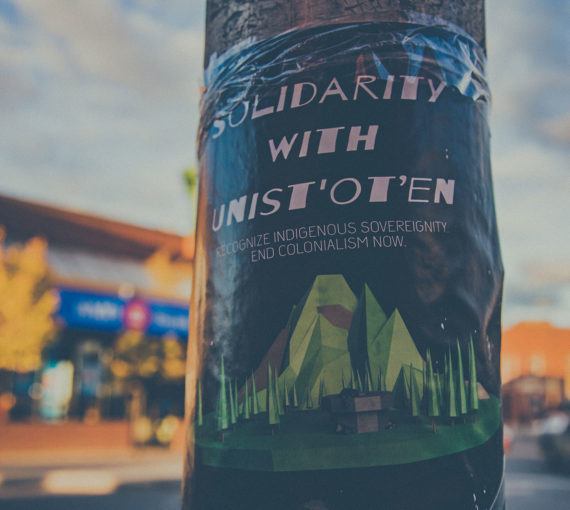

But Canada is changing. Growing recognition of the devastating harms our colonial past and still-existing systemic racism and oppression have perpetrated on Indigenous people has been met with increasing calls to redefine how we see our country, to give land back and to advance systems of economic reparation.

One recent initiative on southern Vancouver Island aims to start decolonizing by creating a forum for businesses and homeowners to make voluntary payments, equal to one per cent of private property taxes a month, to the First Nations whose traditional territories they’re in. The Reciprocity initiative is about creating a way to connect people, return wealth and make territorial recognition tangible. It aims to change the culture of private property and the way people think about home, in Canada and beyond.

“There should be an annual payment that allows First Nations to develop their societies, develop their governments and develop the institutions they need to also help manage those lands.”

The idea of redirecting taxes is not new. In a short video on the future of land governance in Canada, Plenty Canada senior adviser Tim Johnson says that, as Canada’s Parliament buildings stand on unceded Algonquin lands, “I’d rather see the government just say, ‘Yes, we do not legally possess this land; let’s work out a lease arrangement for it.’ There should be an annual payment that allows First Nations to develop their societies, develop their governments and develop the institutions they need to also help manage those lands.”

Another possible change concerns royalties — fees companies pay to provinces in exchange for rights to extract trees, minerals and oil and gas. The system badly needs transforming. B.C. just called for a royalty review for petroleum and gas extraction. Throughout Canada, royalty fees should be increased to reflect externalities — costs not accounted for, such as negative impacts to nature and climate — and should go to First Nations and provincial governments, not to the province alone.

Canada was built on resource extraction, and its foundations are shaky on many fronts, including dispossession of Indigenous Peoples and wilful blindness to natural limits — the surpassing of which has led to the climate and biodiversity crises.

As “Cash Back” says, “It is important that we do not talk about a single ‘economy’ in this country. Because the ‘Canadian economy’ is not the same thing as the many other types of economies that organize Indigenous lives. … Restoring Indigenous economies requires focusing on the perspectives of those most impacted by colonization and the attacks on Indigenous livelihoods. It means reclaiming the language for ‘sharing’ in dozens of Indigenous tongues. It means recognizing that Indigenous inherent rights do not stop at the boundaries of the reserve.”

The sun has set on limitless extraction. Let’s work together to ensure the future is built on economies that sustain and repair, rather than degrade, life.