In June 2021, a precedent-setting court victory for Blueberry River First Nations became the first case in Canada to rule that cumulative impacts of industrial development infringed on Indigenous treaty rights.

Even though most now live in big cities, all people are utterly dependent on and embedded in nature.

Knowledge of this is foundational to Indigenous land stewardship. After a lot of trial and error over millennia, many have learned to live harmoniously with nature, to take only what’s needed, to plan with future generations of humans and other species we depend on in mind.

Supporting Indigenous land governance and lifting up Indigenous knowledge — and valuing it equally with it “Western” scientific understanding — can help protect Earth’s life-support systems.

And these important shifts for Indigenous land rights promise a better way forward for all people in Canada, and for the ecosystems we all depend on.

Many First Nations have tried to seek justice through the courts. Few have won. This ruling creates a path to repair both treaty relationships and the land.

David Suzuki

A historic decision for reconciliation

In June 2021, a precedent-setting court victory for Blueberry River First Nations became the first case in Canada to rule that cumulative impacts of industrial development infringed on Indigenous treaty rights. It could help realize key Truth and Reconciliation Commission calls to action and pave the way for the future of Indigenous land rights.

Resource extraction and agricultural activity have heavily disturbed Treaty 8 territory in the Peace River Valley in northeastern B.C., severely affecting Blueberry’s way of life and ability to hunt.

The Nations spent more than a decade expressing concerns about cumulative impacts to the Oil and Gas Commission, forestry companies and the province. After being bounced between departments or disregarded, they took the province to court in 2018, arguing their treaty rights were breached.

The court ruling creates a path for free, prior and informed consent, and this is the first provincial process to actualize it.

But Blueberry River First Nations’ decision-making authority is still bound by an industrial framework. As a result, 195 forestry, oil and gas projects authorized before the court decision can still go ahead. And 20 proposed projects — all involving development activities in areas of high cultural importance to Blueberry — are on hold pending further negotiations and agreements.

Boreal project manager Rachel Plotkin attended the May, 2019 hearings about the Blueberry River First Nations court case and wrote a five-part series about them:

- Seeking justice: Forestry and oil and gas activity in Blueberry territory has so transformed the landscape, community members can’t pursue their traditional ways of life.

- From “time to time”: Blueberry ancestors were assured their land would only be taken up from “time to time.” But impacts from industrial activity clearly show the bargain has not been upheld.

- The things we cannot see: “In most instances, the present-day landscape completely swallows the historical one.”

- The need for limits: Recovery is often hindered by a lack of knowledge about the habitat disturbance limits a species can withstand.

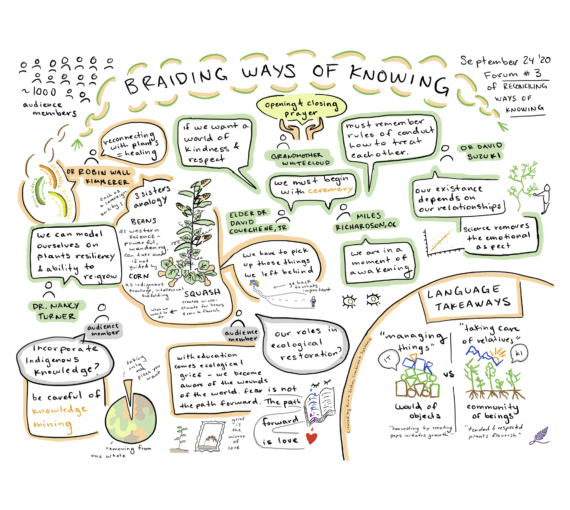

- Restoration as a means of reconciliation: “We need acts of restoration, not only for polluted waters and degraded lands, but also for our relationship to the world.” Robin Wall Kimmerer

The B.C. Supreme Court ruling said the province failed to uphold its treaty promises and outlines a bold new framework for decision-making around resource extraction.

Our Atlas of Cumulative Landscape Disturbance helped convince the Court. It provided critical information about the extraordinarily high levels of industrial disturbance within Blueberry’s traditional territory.

The decision offers renewed hope for Blueberry members, who have watched in sorrow as their land was degraded year after year, and for allies frustrated by provincial adherence to the status quo and limitless resource-extraction approvals that have thrown roadblocks on reconciliation pathways.

It will put Blueberry River First Nations at decision-making tables around industrial extraction and development approvals. It also marks a long overdue, groundbreaking step toward shaping the future of treaty relations.

Allies of Indigenous Peoples should educate themselves and each other, to understand the colonial systems of governance that are root causes for social injustice and environmental crises.

Jesse Wente, Ojibwe journalist

Opening doors for Indigenous governance

We’ve continued to partner with Indigenous communities, including on Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and Indigenous-led restoration and species recovery.

But Indigenous land governance reaches beyond the boundaries of protected areas.

Indigenous Peoples comprise less than five per cent of the world’s population, but protect 80 per cent of the planet’s biodiversity.

Because Indigenous knowledge of lands and waters has evolved over thousands of years, many are looking at Indigenous governance models to help address the global climate and biodiversity crises.

Now the land back movement is gaining increasing attention and support, opening up wider conversations about land governance in Canada.

Learn more through:

- Three short videos exploring Canada’s colonial past, the current Land Back movement and pathways toward a more just future.

- David Suzuki’s Science Matters column “Indigenous Land Back movement charts better way forward”

- This webinar with Indigenous thought leaders and others who share and discuss the videos, Land Governance: Towards a More Just Future.

Act now to help protect nature and promote indigenous rights

Finding Solutions features stories of caring people like you who make everything here possible. You can read, share, discuss, take action, join, donate. Whatever you choose, you’re helping protect Earth’s life-support systems. Thank you.