Helping wild salmon survive and thrive means reducing threats against them — from climate change and pollution to hatchery fish and fish farms. (Photo: Jeffery Young via Flickr)

The wild Pacific salmon story is a compelling illustration of nature’s interconnectedness.

For more than seven million years, the fish have been following a cycle from lakes, streams and rivers, through estuaries and into the Pacific Ocean, where they swim great distances over years, feeding and growing — and facing numerous obstacles to survival.

Once they’ve matured, surviving salmon make the arduous journey upstream, returning to spawning grounds and carrying nitrogen they’ve accumulated in the ocean. Along the way, they feed whales, people, bears, birds and more. Their nitrogen-rich remnants, dragged from the waters by bears and eagles, or pooped out, fertilize the magnificent coastal rainforests.

One significant connection is between Chinook salmon and the beloved but threatened resident Salish Sea orcas, of which only 74 remain. These whales feed exclusively on Chinook. Like sockeye, pink and other salmon, Chinook populations are struggling under a barrage of threats, including climate change, habitat destruction, fishing, pollution and fish farms.

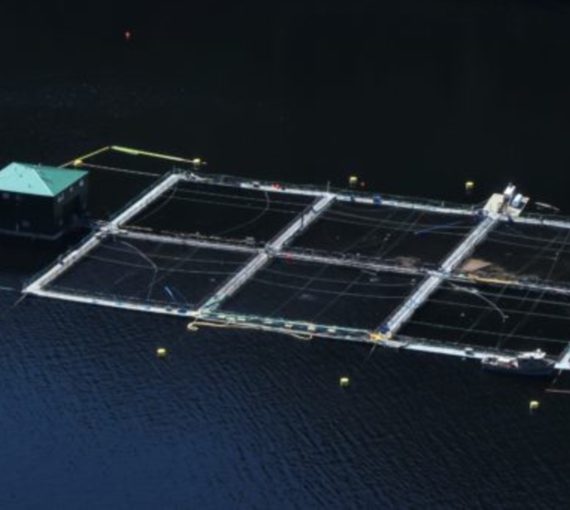

Parasites, disease and potential escapes from open net-pen fish farms put all wild Pacific salmon at risk, including Chinook.

Parasites, disease and potential escapes from open net-pen fish farms put all wild Pacific salmon at risk, including Chinook. Shockingly, this evidence isn’t new — but some has been suppressed for a decade. In 2012, Fisheries and Oceans Canada biologists studied the presence of the highly contagious Piscine orthoreovirus, or PRV, in wild and farmed salmon.

The current federal government has pledged to phase out open net-pen salmon farms in Pacific waters by 2025, but it and previous governments kept this study under wraps until March, when it was finally released after a multi-year access-to-information challenge from Wild First.

PRV causes anemia and jaundice in farmed salmon and can spread to wild salmon. The study found it’s uniquely damaging to Chinook, causing their blood cells to rupture, leading to kidney and liver damage. The virus is not native to B.C. waters, but has been found in Atlantic salmon — the kind farmed in B.C.

A 2021 University of British Columbia study confirmed that farmed fish are transferring PRV to wild salmon, and found that proximity to fish farms increases the likelihood of wild Chinook being infected. One of the original DFO study’s authors, federal biologist Kristi Miller-Saunders, called the delay a “travesty” that has contributed to ongoing doubt about viral impacts of fish farms on wild salmon.

A 2021 University of British Columbia study confirmed that farmed fish are transferring PRV to wild salmon, and found that proximity to fish farms increases the likelihood of wild Chinook being infected.

That doubt has led to concerted effort by the aquaculture industry and its supporters to push back against the government’s plans to phase out the farms. They argue it will mean killing millions of farmed salmon and cause numerous job losses.

But, as independent biologist Alexandra Morton — who has studied the fish for 30 years — told the Guardian, “Industry should have known this was coming and seen the writing on the walls. They should have started transitioning to different kinds of enclosures. Instead, they relied for years on the government — on the department of fisheries and oceans — to hide their sins.”

Morton and other biologists have argued that farmed salmon can also transfer potentially lethal sea lice and mouth rot to wild salmon.

The department said it based its decision to withhold the report on disagreement among groups participating in the study, which it funded with the Aquaculture Collaborative Research and Development Program and salmon producer Creative Salmon. But in ordering the department to release it, the federal information commissioner said Wild First’s challenge was “well-founded” and suppressing the report wasn’t justified.

Despite some setbacks, the federal government now appears to be taking salmon (and orca) conservation seriously, and is sticking to its plan to phase out the farms — something the public should support.

It’s a problem when the federal department charged with looking out for wild salmon is also supporting the aquaculture industry’s interests. As is often the case, short-term economic arguments win out over immediate and long-term environmental protection. But wild salmon — and the orcas, bears, eagles, rainforests and people they support — are too important to sacrifice to profits for a damaging industry that should clean up its act.

Despite some setbacks, the federal government now appears to be taking salmon (and orca) conservation seriously, and is sticking to its plan to phase out the farms — something the public should support. If salmon are farmed, they should be raised in closed-containment operations, preferably on land, with attention paid to reducing or eliminating any other environmental impacts.

Helping wild salmon survive and thrive means reducing threats against them — from climate change and pollution to hatchery fish and fish farms.