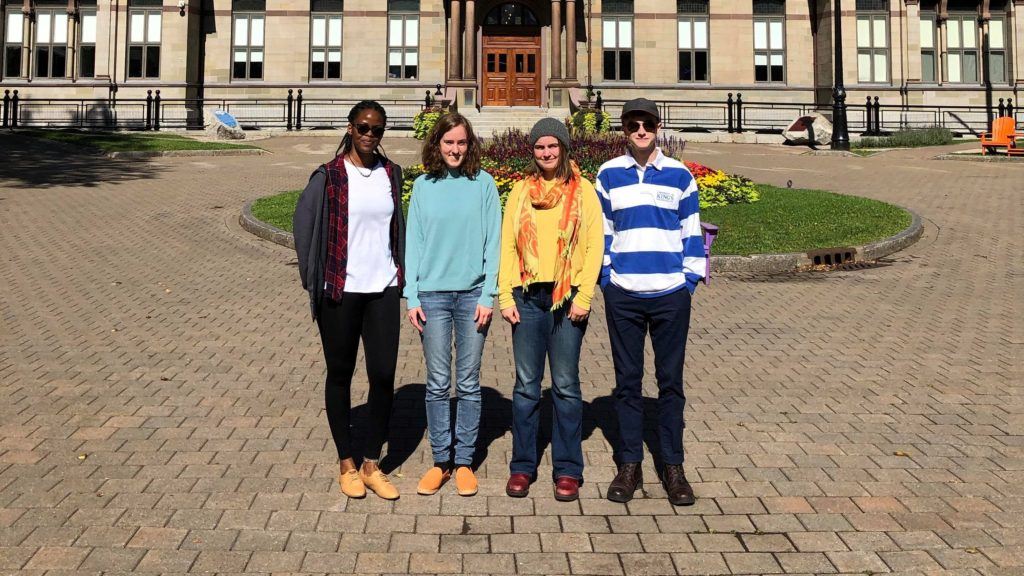

Youth climate advocates outside City Hall. From left to right: Neria Atwine, Erin Appelbe, Lily Barraclough, and Cameron Yetman.

HalifACT 2050, Halifax Regional Municipality’s climate action plan, is currently one of the most ambitious climate plans in Canada. That’s due in no small part to the interest and passion of the municipality’s residents, and in particular, a group of determined young climate advocates.

Lily Barraclough is one of those instrumental young leaders. Currently a master’s student at Dalhousie University researching politically active youth and climate grief, she became interested in municipal politics as a high school student in Toronto, while leading the Toronto Youth Environmental Council. In 2015, Lily trained as a Climate Reality Project leader, which led her to connect with iMatter Youth, an organization that helps young people take climate action in their communities. She went on to lead the Canadian branch of iMatter Youth, and when she moved to Halifax for her undergraduate degree, she started a local chapter there.

You don’t have to know absolutely everything before presenting to council or meeting with councillors. It’s their job to listen to you because they represent residents in the municipality.

Lily Barraclough

In 2016, Lily and other young climate leaders presented Halifax council with a climate report card, assessing it on climate action from a youth perspective. They were disappointed in the council’s response.

“Council passed us to the staff, who were basically like, ‘We can’t do anything without directives from council,’” Lily recalls. “The staff told us to go back and meet with council. It was a lot of patting us on the head and saying, ‘Thank you for coming,’ and not a lot of action.”

Unimpressed but undeterred, the group decided to change tack and focus on establishing an official venue for youth to influence municipal decision-making. They drew up a proposal to create a youth advisory committee, which council accepted in 2017.

“That was a really big step because previously there weren’t any formal ways for youth to be involved,” Lily says. “The youth advisory committee got a lot of media coverage and a lot of interest from different aspects of Halifax. That made it clear to council that it was important. After that, I noticed a shift in how they were responding to us.”

In partnership with other organizations and individuals, iMatter Halifax then began to draw up a climate inheritance resolution, which declared that as the future inheritors of the planet, young people (along with marginalized communities) will experience the worst impacts of climate change. The resolution asked council to create a strong climate plan for Halifax, and when presented with it, council agreed. iMatter worked with municipal staff to draft a climate plan proposal. Once it passed, they were invited to take part in the planning process as official stakeholders, alongside industry, academic, nonprofit, utilities and government representatives, as well as the Mi’kmaq, African Nova Scotian communities and Acadian groups.

“It was a very eye-opening experience because such a wide variety of people were brought in,” says Lily, who was one of only two youth representatives. “It was quite a responsibility to know that if we didn’t show up, then there wouldn’t be a youth voice. So I made a big effort to go to those meetings.”

Chaz Garraway, an engineering student at Dalhousie University, was the second youth representative. He explains that they participated in several sessions, first gauging how all the stakeholders felt about taking climate action, then brainstorming potential solutions for curbing emissions and obstacles to reaching emissions reduction targets. He recalls “a lot of collaboration” in the diverse group of representatives.

Don’t be afraid if what you do day-to-day isn’t about the environment or climate change. That doesn’t mean you don’t have a role to play.

Chaz Garraway

The result of those sessions (along with public consultations, presentations, surveys and conversations led by municipal staff) was HalifACT 2050, released in early 2020. It has been praised for its emissions reduction targets — 75 per cent below 2016 levels by 2030, and 95 per cent below 2016 levels by 2050 — and called the most ambitious plan in Canada.

“It’s getting a lot of community engagement,” Chaz says. “People are supportive of the plan.”

When asked what advice he might offer folks wanting to work with their municipal governments on climate action, Chaz says that when he moved to Halifax for university, he didn’t know how to get involved in climate action. He began by simply Googling “climate action in Halifax.” That led him to connect with iMatter Youth, as well as a climate action club at Dalhousie and professors working on the issue.

His advice: “Just pick something, whether it’s transportation or renewable energy. Find how you can get involved in your community, and just start. Once you start, you really don’t know where it’s going to take you.” His climate journey has taken him to Los Angeles to train as a Climate Reality leader, to New York to speak at the UN Climate Change Summit and to the Caribbean, where he is the youth lead and 1,000,000 Caribbean Tree Planting Project co-leader with the Caribbean Philanthropic Alliance.

“Don’t be afraid if what you do day-to-day isn’t about the environment or climate change. That doesn’t mean you don’t have a role to play,” he says.

Asked the same question, Lily says, “You don’t have to know absolutely everything before presenting to council or meeting with councillors. It’s their job to listen to you because they represent residents in the municipality. To me that was really empowering because often it’s scary to question authority figures, especially as a young person. But they’re the ones who should be worried about answering our questions, because they’re the ones not doing enough, not us.”

She adds that it was important to learn to tell her story in a way that resonated with council members and media. “The human connection is the most important thing because decision-makers have had the facts for many years. The facts aren’t what changes their minds.”

Lily learned about effective storytelling, as well as speaking with media, climate science and presenting to council from iMatter’s online resource library. She notes that Our Time also offers resources for youth wanting to work with municipal governments, but on the whole, such educational resources are lacking in Canada.

“Everything I learned, I learned by myself or through iMatter,” she says. “I did not learn it in school at all. There’s a lack of civic education, especially around municipal issues. Like, I didn’t know you could go present to city council or that you can just write your representative at any level of government and ask for a meeting. I don’t think people know that. People don’t realize that your elected representatives are your representatives, so you have access to them. And if you don’t, that’s a problem, and you should elect someone else.”

Renewable energy is empowering communities across the country. Charged Up is the story of you — of all of us — on a mission for a cleaner, healthier charged-up Canada.