In May 2019, the Blueberry River First Nations court case against the province began: the case focuses on the fact that the cumulative impact of industrial activities has significantly impacted the lands and wildlife within Blueberry’s traditional territory and, accordingly, their treaty rights.

I was surprised during opening remarks to hear that signing treaties was described in previous Supreme Court rulings as an early form of reconciliation:

Treaties serve to reconcile pre-existing Aboriginal sovereignty with assumed Crown sovereignty, and to define Aboriginal rights guaranteed by s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. Section 35.

In many ways, that statement packs a punch, as it recognizes Indigenous sovereignty and qualifies the Crown’s sovereignty as “assumed.”

Yet, as time has passed, we have failed to honour Indigenous sovereignty. That’s what this court case is about. Now, reconciliation has come to mean many different things.

For some, like Leanne Simpson, it means land repatriation: “If reconciliation is to be meaningful…It means giving back land, so we can rebuild and recover from the losses of the last four centuries and truly enter into a new relationship with Canada and Canadians.”

For other Indigenous Peoples, sovereignty can be put into practice through governance, or co-governance, of Indigenous Protected Areas (often called tribal parks in B.C.).

The remedy that Blueberry First Nation calls for, among other measures, is restoration.

In the words of Giltrow:

The Plaintiffs will contend that solutions are possible. That despite the significant level of development in the territory, and the impacts of that development on the exercise of Treaty rights, measures are available and at hand to quell the rate of new disturbance on the landscape, protect important areas and ecosystems, and to begin to restore the areas already impacted. Remedy can be meaningful.

(Note that the province referenced restoration too: their lawyer stated, “The evidence will show that many forms of taking up may be temporary. Restoration and return to pre-development status must also be considered.” I can’t help but be a bit cynical in thinking that the province’s view of restoration is akin to something like: “Oh, just let us keep working with industry to extract resources as fast as we want, wherever we want, and we’ll get industry to fix it later, we promise,” not unlike the scenario playing out with orphaned wells in the province.)

Vague references to ‘consider’ restoration are not what is needed. As a recent report from the David Suzuki Foundation outlines:

- Range-scale restoration of legacy industrial disturbance is critical;

- Funds should be posted by industry and government to cover their respective restoration obligations; and

- More progressive restoration directives that exceed the need to merely revegetate the land must be developed.

The report also recommends that investments should be made in Indigenous-led restoration initiatives.

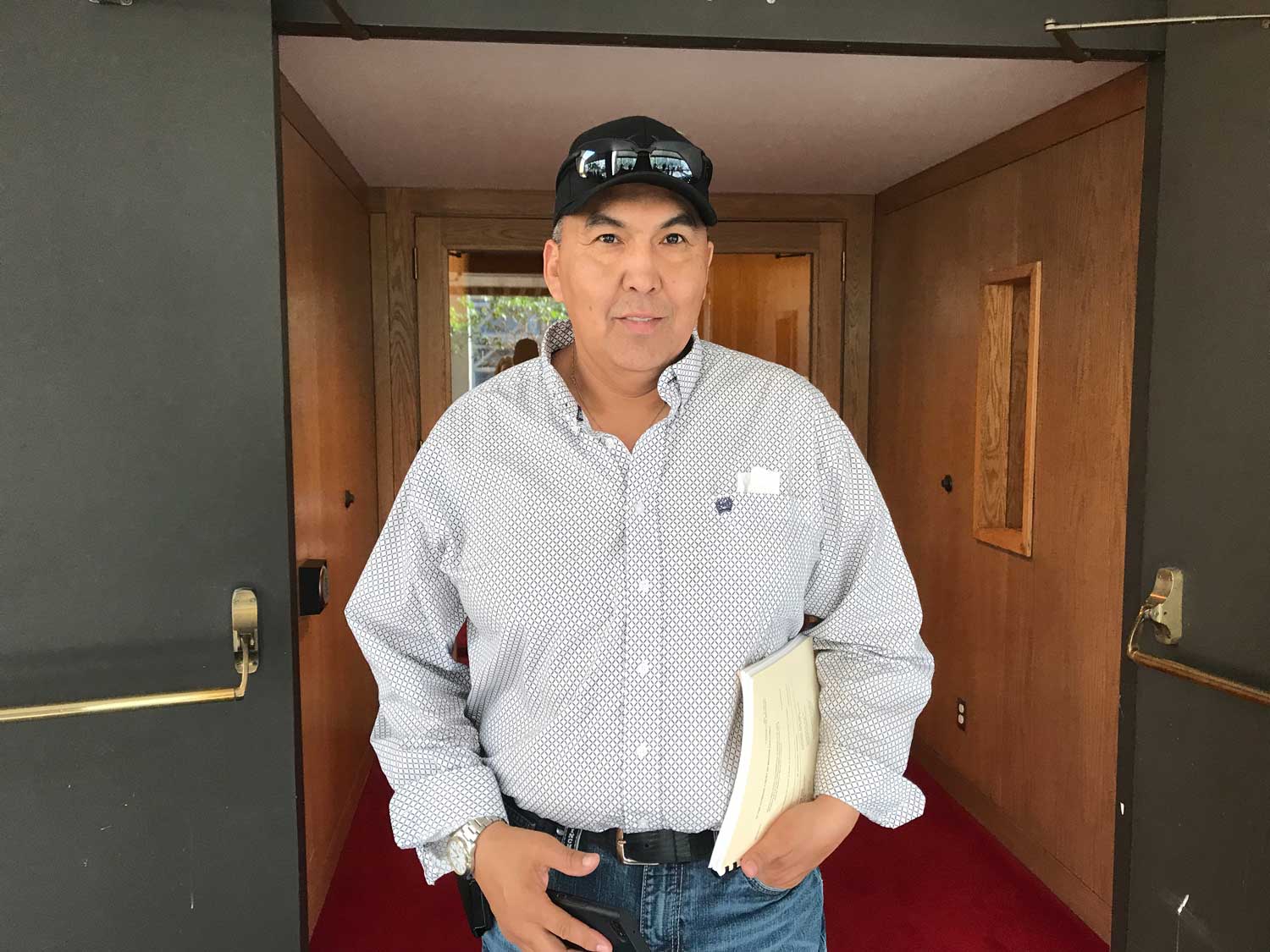

Chief Marvin Yahey outside the courtroom where opening remarks were heard.

I spoke with Chief Marvin Yahey about the potential power of restoration. He articulated the belief that restoration can not only heal the land, but can also help to advance reconciliation.

In many ways, restoration offers a bundle of healing, and of hope. According to Marilyn Baptiste, former Chief of the Xeni Gwet’in First Nation, “The thing we need to look to is the healing of our people, and we can’t do it without our land and water. That’s a part of this tribal park process.”

Restoration can facilitate repair of landscapes fractured by our activities, and our relationships with Indigenous Peoples whose culture depends on them.

According to Giltrow, redressing activities that have impaired the Crown’s ability to uphold the promises made under the treaty requires another form of reconciliation: that of the duty and power held by the Crown.

In many ways this mirrors the challenge before us all. We have shown that we have the power to degrade the planet. What is lacking is demonstration of our sense of responsibility, or duty, to repair it.

I believe restoration projects can foster a change in our own relationship with the nature. In the words of Robin Kimmerer, “We need acts of restoration, not only for polluted waters and degraded lands, but also for our relationship to the world.”

Perhaps restoration can foster a more reciprocal relationship with our planet — one in which our own taking up is offset by giving back.

This is the fifth article in a five part series on the legal challenge by Blueberry River First Nations against the Province of B.C. over treaty rights infringement.

Our work

Always grounded in sound evidence, the David Suzuki Foundation empowers people to take action in their communities on the environmental challenges we collectively face.