(Photo: Centre for Whale Research)

These iconic species usually come home in spring, but they’re a rare sight in B.C. waters so far.

As we stretch into the latter half of summer, it’s a good time to reflect on what we have seen of the Salish Sea orcas and their Chinook salmon prey. Sightings of the iconic southern resident orcas have been few and far between for the second year in a row. Just as last year, the whales seem to be mostly staying out of the Salish Sea. Is this the new normal? Southern resident orcas usually come into the Salish Sea in spring, spending most of the spring and summer feeding on Chinook salmon. Scientists are speculating they are spending less time in the Salish Sea because of poor wild Chinook salmon returns to the Fraser River and other streams around the Salish Sea.

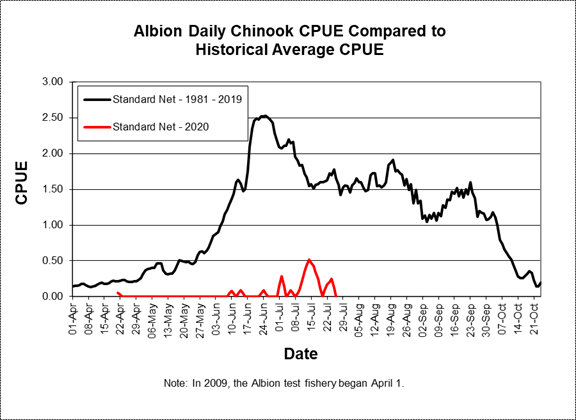

Figure 1

Chinook salmon returns to the Fraser River are drastically low this year. The Albion test fishery is designed to monitor Chinook migrating up the Fraser River and provides the best in-season indicator of abundance. This year, it has recorded only six Chinook. Compare this to the historical average of hundreds and you can see this species is in trouble (see figure 1).

Most of these Chinook populations were identified as threatened or endangered even before this year’s poor returns. Now the Big Bar landslide is limiting their ability to reach spawning grounds. Some early Chinook runs are encountering high flows at the Big Bar landslide and are struggling to get past it to spawning grounds. Because the southern resident killer whales feed on local Chinook salmon, they have remained in this area, which is why they are known as “residents.”

Most of these Chinook populations were identified as threatened or endangered even before this year’s poor returns.

The recent good news is that drone imagery shows a few of the orcas are pregnant. It is not unusual and it’s too early to celebrate. Two-thirds of pregnancies in the southern resident orca pods fail. To have healthy babies, expecting orca moms need a lot of quiet and an abundance of Chinook salmon. In recent years both have been scarce.

Initially, many scientists thought COVID-19 would reduce vessel traffic and recreational Chinook fishing. However, small boat sales are up and Fisheries and Oceans Canada is monitoring the recreational fishery less than in previous years. Thus, we don’t really know whether impacts from vessel noise or fishing have truly diminished. The good news is that earlier this year Transport Canada enacted a rule requiring boats to keep 400 metres away from southern resident orcas throughout their Canadian distribution.

Ultimately, until each of these major threats is addressed, orcas will continue swimming toward extinction.

Despite the challenges Salish Sea orcas face, we are still seeing whale-watching groups in the U.S. and recreational anglers in Canada resisting efforts to protect orcas and the Chinook salmon they need to survive. The government is also set to decide whether to allow a major expansion to a shipping port south of Vancouver in the critical estuary habitat of many Fraser Chinook salmon runs. Ultimately, until each of these major threats is addressed, orcas will continue swimming toward extinction. Rather than playing the blame game, those responsible for impacts on Chinook and orca must recognize their role and act to ensure recovery of these whales and fish.

Our Work

Always grounded in sound evidence, the David Suzuki Foundation empowers people to take action in their communities on the environmental challenges we collectively face.