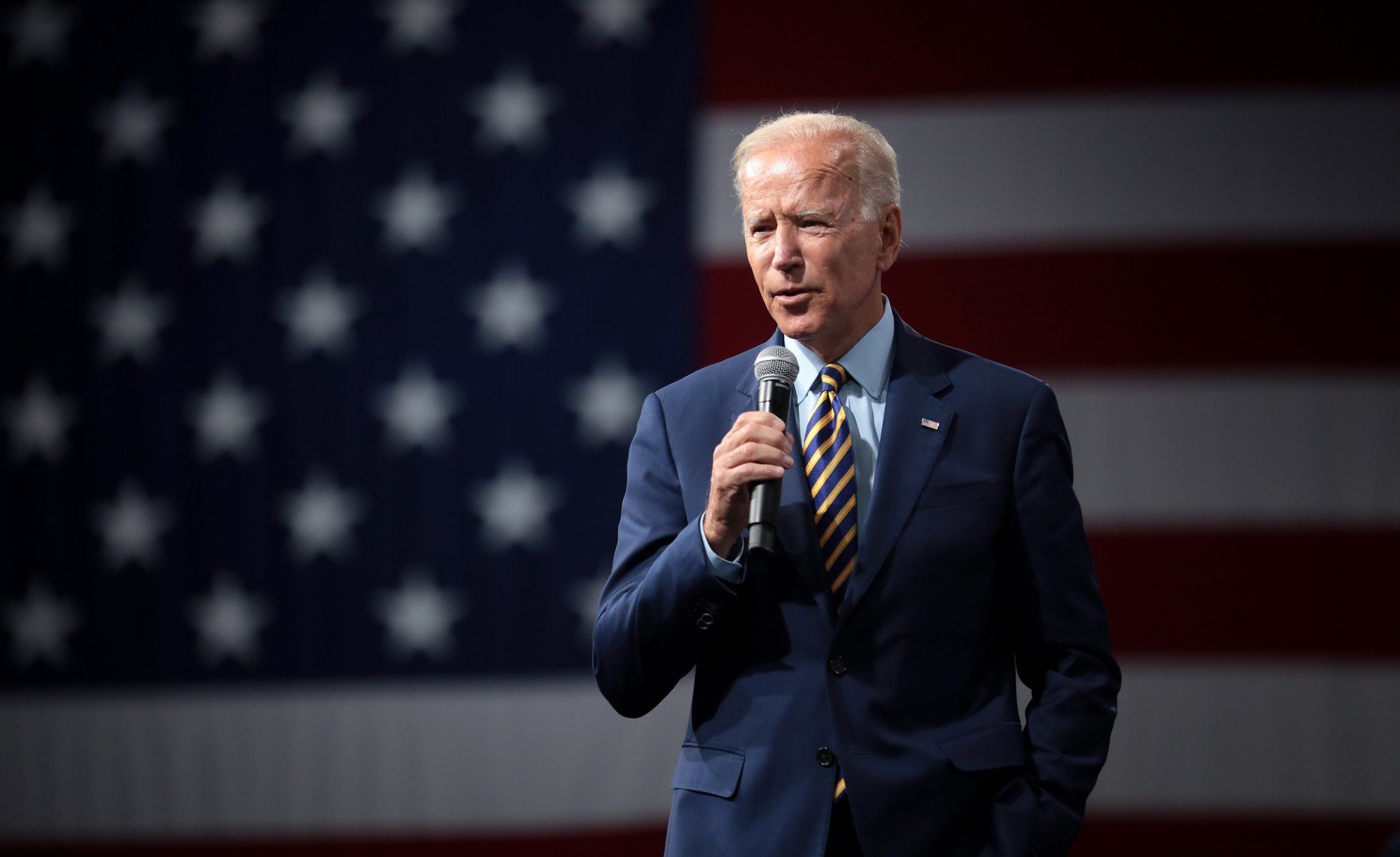

The president’s Day 1 executive order on the environment directed federal agencies to immediately review regulations to ensure consistency with specified “important national objectives.; (Photo: Gage Skidmore via Flickr)

In 1967, Northern Pulp started discharging wastewater in Boat Harbour, N.S. After a ruptured pipe spilled untreated effluent into a wetland in 2014, the Pictou Landing First Nation set up a road blockade, but it would be another six years before the province closed the mill in 2020.

It’s one example of “environmental racism” documented by the ENRICH Project, a collaborative, community-based program investigating toxic industries near Mi’kmaq and Black Nova Scotian communities.

Canada has ignored environmental racism for too long. That may be about to change. Cumberland-Colchester MP Lenore Zann recently introduced Bill C-230, the National Strategy to Redress Environmental Racism Act, in the House of Commons. It’s scheduled for a March vote.

Canada can look to the new U.S. administration for inspiration. While many are focusing on U.S. President Joe Biden’s commitment to climate action, a plan “to secure environmental justice” has received less attention.

The president’s Day 1 executive order on the environment directed federal agencies to immediately review regulations to ensure consistency with specified “important national objectives,” including prioritizing environmental justice and holding polluters accountable for disproportionate harm to communities of colour and low-income communities.

He also plans to revise the 1994 executive order on environmental justice “to address current and historic environmental injustice.”

Environmental justice has long been a blind spot in Canadian law and governance, and Canada remains one of the few countries to not formally recognize the human right to a healthy environment.

Canadian lawmakers should take note. Environmental justice has long been a blind spot in Canadian law and governance, and Canada remains one of the few countries to not formally recognize the human right to a healthy environment.

Bill C-230 presents an opportunity for Canada to align with the new U.S. administration’s emphasis on environmental justice and signal a commitment to placing equity considerations at the centre of the environment agenda.

Environmental racism occurs when environmental policies or practices intentionally or unintentionally result in disproportionate negative impacts on certain individuals, groups or communities based on race or colour. For example, through placement of polluting industries or other environmentally dangerous projects. Affected communities often lack the political power to influence siting decisions or advocate for stronger standards.

In speaking to her bill, Zann mentioned landfills affecting African Nova Scotia communities in Shelburne and a pipeline on the Sipekne’katik First Nation, as well as the pulp and paper mill near Pictou Landing First Nation.

In the African-Nova Scotia neighbourhood of Shelburne, some homes are within 150 metres of a landfill that operated for 75 years before closing in 2016. “We all have the same [feelings] and fears about what we were exposed to when we grew up, the many deaths from cancer we experience, the exceptionally high number of men that passed away before they turned 70,” says community member and ENRICH Project participant Louise Delise.

On the Sipekne’katik First Nation, Alton Natural Gas Storage began constructing a brine discharge pipeline on unceded land near the Shubenacadie River in 2014. The project would allow natural gas storage in underground salt caverns. Mi’kmaw water protectors oppose the project and Sipekne’katik First Nation claims it wasn’t adequately consulted and didn’t give consent. A four-year court battle culminated with the Nova Scotia Supreme Court overturning provincial approval for the project in March, ordering the province to resume consultations with Sipekne’katik First Nation.

Bill C-230 would require the federal environment minister, Jonathan Wilkinson, to collect information about locations of environmental hazards like these, as well as negative health outcomes in affected communities, and examine the link between race, socio-economic status, and environmental risk.

Paralleling aspects of Biden’s environmental justice agenda, Bill C-230 would require the federal environment minister, Jonathan Wilkinson, to collect information about locations of environmental hazards like these, as well as negative health outcomes in affected communities, and examine the link between race, socio-economic status, and environmental risk. The bill mandates development of a national strategy to redress environmental racism and consideration of possible amendments to federal laws, policies and programs to address it.

This is more urgent than ever. To quote Biden’s plan, “the current COVID-19 pandemic reminds us how profoundly the energy and environmental policy decisions of the past have failed communities of color — allowing systemic shocks, persistent stressors, and pandemics to disproportionately impact communities of color and low-income communities. … Any sound energy and environmental policy must … recognize that communities of color and low-income communities have faced disproportionate harm from climate change and environmental contaminants for decades.”

Canada must join the U.S. in seeking to embed environmental justice and rights in decision-making, while recognizing and redressing historic failures to do so. All-party support for Bill C-230 would be a good start. Government has also promised to modernize the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, another important opportunity to introduce environmental justice requirements.

All people in Canada have the right to a healthy environment. To make this reality, we must take deliberate action to redress and prevent environmental racism.

This op-ed was originally published in The Hill Times

Our Work

Always grounded in sound evidence, the David Suzuki Foundation empowers people to take action in their communities on the environmental challenges we collectively face.