The Taku’s importance only grows in this time of climate change, species loss and dwindling salmon runs. (Photo: Bruce Barrett via Flickr)

B.C. has had plenty of time — 65 years — to get it right on the Tulsequah Chief mine south of Atlin. Although the provincial government finally appears poised to do what’s needed, the Tulsequah and Taku rivers are not yet in the clear.

Closing and cleaning up the long-abandoned, polluting copper-lead-zinc mine will be good all around: for the Taku River watershed, for our province and Alaska, which share that watershed, for the people who call it home, and for sustaining the outstanding ecological and cultural values that make the area so special.

My family and I had the opportunity to take part in a memorable Taku rafting expedition in 1998. Embracing the northwest B.C. traditional territory of the Taku River Tlingit First Nation, the remote 1.8-million-hectare Taku watershed is said to be the largest intact river system on North America’s Pacific Coast and, except for its Tulsequah Chief problem, is pristine. To immerse ourselves in the Taku’s wilderness splendour was life-changing. As I’ve come to appreciate, the conservation attributes of this watershed are of truly planetary significance. As a complete, diverse, resilient mountains-to-sea ecosystem, the Taku’s importance only grows in this time of climate change, species loss and dwindling salmon runs.

As I’ve come to appreciate, the conservation attributes of this watershed are of truly planetary significance.

Like others who have experienced the Taku, I’ve followed its mining issues closely, both the toxic acidic wastewater discharging from the old Tulsequah Chief mine, unabated since 1957, and the prospect of a new bigger mine development by the same name targeting the same area. Previous owner Chieftain Metals started redevelopment work, but was placed into receivership in 2016. Close to the Alaska border, a new mine would be immediately above some of the watershed’s foremost salmon-spawning and -rearing habitat.

The old mine’s pollution and the prospect of new mining in its place have been matters of intense concern and opposition among Indigenous communities on both sides of the border. For the Taku River Tlingit, the threat of a road punched through the heart of its territory to serve a new mine, bringing more development with it, has been particularly troublesome. Commercial fishing interests have also been standing up for the Taku, the transboundary region’s top salmon producer. As the downstream recipient of Tulsequah Chief’s toxic discharge, the state of Alaska has long been calling for redress on this issue as well. Finally, these voices have been heard.

The old mine’s pollution and the prospect of new mining in its place have been matters of intense concern and opposition among Indigenous communities on both sides of the border.

Unfortunately, while B.C. seems prepared to do the right thing, little is happening. When former Mines Minister Bill Bennett declared Tulsequah Chief’s pollution unacceptable in summer 2015, few of us would have thought that, seven years after this welcome pronouncement, we would still only be talking about remediation. It’s a complex and expensive problem, for sure, warranting extensive planning. But the time has come for action.

B.C. has yet to issue a mine closure and clean-up plan. It has yet to secure funds for the work. It’s not being transparent about its intentions. And the receivership status of bankrupt Chieftain Metals, which holds the environmental certificate for Tulsequah Chief, has yet to be terminated. On that last point, even though the Taku River Tlingit asked the court not to extend the receivership, B.C. did not object to the extension, and used it as an excuse for not taking more aggressive action.

The Taku deserves better. Ongoing problems with the old mine illustrate some of the dangers of building a new mine in its place. If B.C. really wants to demonstrate responsible and progressive oversight of mining in the province — especially after the disastrous 2014 Mount Polley tailings spill — Tulsequah Chief is the place to start. It’s time.

This op-ed was originally published in The Province

Our work

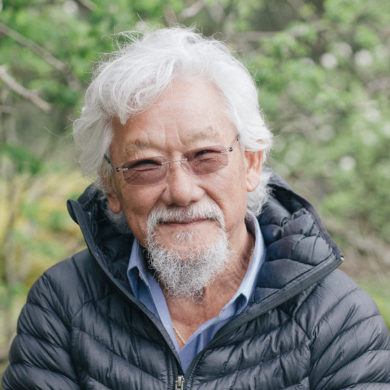

Always grounded in sound evidence, the David Suzuki Foundation empowers people to take action in their communities on the environmental challenges we collectively face.