I’m sure in today’s COVID-19 lockdown, despite all of the technologies we have to occupy us, computers, television, cellphones, many of us are feeling profound isolation, loneliness and boredom.

But this big slowdown gives me time every day to play with my grandchildren who are isolated with me, to read and to think about what has mattered most in my life, what has given me the greatest joy and satisfaction, and where I hope the world might go after I’m gone.

The lessons of pandemics

I remember when the HIV-AIDS crisis first happened. It was terrifying because the disease was so deadly and we didn’t know what was causing it or how it was transmitted.

We did a film on it in the early years for The Nature of Things and traveled to Boston to interview a man dying of AIDS and his partner. I’m embarrassed to say that I was scared out of my mind doing that interview because we knew so little about it then.

In the timescale of scientific research, astonishingly rapid insights were gained into the cause and mode of transmission of this disease. But it did take years and AIDS was a devastating tragedy for the individuals and communities involved.

We learned that HIV was transmitted through blood and semen, so while still lethal and, at the time, without a treatment, it was preventable by changing behaviour – safe sex and clean needles. Unfortunately, this change proved to be a difficult obstacle.

And it remains the most difficult challenge with environmental issues — learning to see our place in the world differently so we can make changes in our destructive behaviours.

Difficult as it is now, this pandemic will subside and we will learn some profound lessons from the experience.

Difficult as it is now, this pandemic will subside and we will learn some profound lessons from the experience. It may provide a chance to reset priorities and direction for ourselves and society.

It is a universal challenge for all human beings. As B.C.’s Indigenous people say, “We’re all in the same canoe and we have to paddle together if we want to reach our goal.”

Finding hope in moments of crisis

My parents married in the 1930s during the Great Depression. Those were hard times but Mom and Dad would say that what got them through was hard work, family and community.

And they told me repeatedly, “You have to work hard for the necessities in life, but you don’t run after money as if having a new car, a big house or fancy clothes makes you a better or more important person.”

That has guided me all my life and I have drummed it into each of my children — that money is not the goal of our existence rather the goal is a life well lived.

If we could take a different path from our current one — in which more, bigger and newer seem to drive our purchases, wherein the idea of consumption for the sake of the economy and the impossible dream that endless growth is both possible and necessary for progress — we might move toward a very different future.

In this moment of crisis, we should be asking what an economy is for, whether there are limits, how much is enough and whether we are happier with all this stuff.

In this moment of crisis, we should be asking what an economy is for, whether there are limits, how much is enough and whether we are happier with all this stuff.

Can we relearn what humanity has known since our very beginnings — that we live in a complex web of relationships in which our very survival and well-being depend upon clean air, water and soil, sunlight (photosynthesis) and the diversity of species of plants and animals that we share this planet with?

Can we establish a far more modest agenda for ourselves filled with reverence for the rest of creation?

Or will we celebrate the passing of the pandemic with an orgy of consumption and a drive to get back to the way things were before the crisis?

For me, one of the most dramatic effects of humanity’s COVID-19-induced slowdown has been nature’s rapid response; clean air over China, fish in the canals of Venice and the sighting of a raptor in my Vancouver backyard.

In this disaster lies an opportunity to reflect and change direction in the hope that if we do, nature will be far more generous than we deserve.

This op-ed was originally published on CBC

Our Work

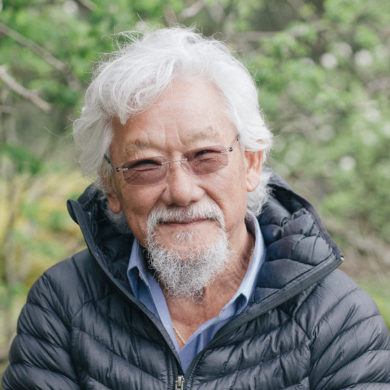

Always grounded in sound evidence, the David Suzuki Foundation empowers people to take action in their communities on the environmental challenges we collectively face.